- Home

- Nathaniel Hawthorne

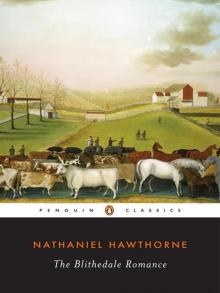

The Blithedale Romance

The Blithedale Romance Read online

Table of Contents

PENGUINCLASSICS

Title Page

Copyright Page

Introduction

PREFACE

THE BLITHEDALE ROMANCE

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

NOTES

PENGUINCLASSICS

THE BLITHEDALE ROMANCE

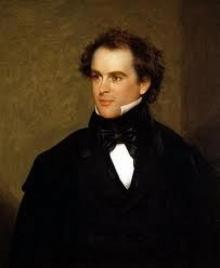

NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE (1804-1864) was born in Salem, Massachusetts, where, after his graduation from Bowdoin College in Maine, he wrote the bulk of his masterful tales of American colonial history, many of which were collected in his Twice-told Tales (1837). In 1839 and 1840 Hawthorne worked in the Boston Customs House, then spent most of 1841 at the experimental community of Brook Farm. After his marriage to Sophia Peabody, he settled in the “Old Manse” in Concord; there, between 1842 and 1845, he wrote most of the tales gathered in Mosses from an Old Manse (1846). His career as a novelist began with The Scarlett Letter (1850), whose famous preface recalls his 1846-1849 service in “The Custom-House” of Salem. The House of the Seven Gables (1851) and The Blithedale Romance (1852) followed in rapid succession. After a third political appointment—this time as American Consul in Liverpool, England, from 1853 to 1857—Hawthorne’s life was marked by the publication of The Marble Faun (1860) but also by a sad inability to complete several more long romances. III health surely accounts for some of this. But as the north and south plunged into Civil War, the specter of national fratricide may have finally eroded Hawthorne’s ability to create imaginative or moral sense out of America’s now ambiguous and very bloody present history.

ANNETTE KOLODNY is the author of The Lay of the Land: Metaphor as Experience and History in American Life and Letters and The Land Before Her: Fantasy and Experience of the American Frontiers, 1630- 1860, as well as many articles on American culture and American literary history that have appeared in various journals and essay collections. Following her years as Dean of the College of Humanities at the University of Arizona, she published Failing the Future: A Dean Looks at Higher Education in the Twenty-first Century. Her several honors and awards include the Florence Howe Prize for Feminist Literary Criticism, the Jay B. Hubbell Medal for Distinguished Scholarship in American Literary Studies, the Western Literature Association’s Distinguished Achievement Award, and designation as an Honored Scholar by the Early American Literature Division of the Modern Language Association.

The text of The Blithedale Romance

is that of the Centenary Edition

of the Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne,

a publication of the

Ohio State University Center for Textual Studies

and the Ohio State University Press.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R oRL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R oRL, England

First published in Great Britain by Chapman and Hall 1852

First published in the United States of America by Ticknor, Reed, and Fields 1852

This text of The Blithedale Romance first published by Ohio State University Press, 1964

Published in The Penguin American Library 1983 Reprinted 1985

The text of The Blithedale Romance copyright ©

Ohio State University Press, 1964

Introduction and Notes copyright © Viking Penguin Inc., 1983

All rights reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Hawthorne, Nathaniel, 1804-1864.

The Blithedale romance.

(Penguin Classics)

“First published in Great Britain by Chapman and Hall, 1852.”—Verso t.p.

Text of the Blithedale Romance originally published as v. 3 of the

Centenary edition of the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Columbus,

Ohio State University Press, C1962-

Bibliography: p.

I. Kolodny, Annette, 1941- II. Hawthorne,

Nathaniel, 1804-1864. Works. 1962. III. Title.

PS1855.A’.3 83-8031

ISBN: 9781101077900

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other

means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please

purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage

electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

http://us.penguingroup.com

Version_3

INTRODUCTION

In April of 1841, braving leaden skies and a threatening snowstorm, Nathaniel Hawthorne walked the nine miles from Boston to an isolated farmhouse on the Dedham-Watertown Road in West Roxbury, Massachusetts. His destination was Brook Farm, an experimental socialist community envisioned by its founders as “a society of liberal, intelligent and cultivated persons, whose relations with each other would permit a more wholesome and simple life than can be led amidst the pressures of our competitive institutions.” Here Hawthorne hoped to find a secure home for himself and his fiancée, Sophia Peabody of Salem, as well as a haven in which to concentrate on his writing. He was almost thirty-seven years old. And although he had long ago determined to earn his living by his pen, he had as yet produced one slight novel (Fanshawe: A Tale, published anonymously at his own expense in 1828), a collection of previously published tales and sketches (Twice-Told Tales, 1837), and an assemblage of New England historical tales for children (Grandfather’s Chair, 1841). In the spring of 1841, then, having quit his job as the measurer of salt and coal at the Boston Custom House because it interfered with his writing, he was eager to get on both with his life and with his chosen life’s work.

Ten years later, in the summer of 1851, Hawthorne decided to “take the Community for a subject.” He was now an established writer, with The Scarlet Letter (1850), The House of the Seven Gables (1851), and two successful collections of tales and sketches to his credit. Brook Farm was no more. Financial difficulties had plagued it from its inception and, after a devastating fire in 1846, the entire experiment was abandoned in the spring of 1847.

Hawth

orne himself, moreover, had only briefly been a participant in the Brook Farm experiment. Determined, along with the others, to give “my best efforts” to the enterprise, he found himself putting in eight- and ten-hour days to ensure the farm’s initial solvency. This was hardly the three-hour workday that the founders of the little community had anticipated. Soon after his arrival, therefore, Hawthorne admitted in a letter to a friend that the long hours in the barn and out in the fields had resulted in “the sacrifice of some objects that I had hoped to accomplish.” By June he was complaining in letters to Sophia that “this present life of mine gives me an antipathy to pen and ink, even more than my Custom-House experience did.” A brief respite from the farm in September left him persuaded that his “life there was an unnatural and unsuitable” one for him. And, upon returning to Brook Farm later that month, he became a paying “boarder,” rather than a workingman, but still found himself unable to write. “I have not the sense of perfect seclusion, which has always been essential to my power of producing anything,” he explained to Sophia. It was not that anyone actually intruded upon his privacy, he continued. It was that in the excited atmosphere of the Brook Farm experiment, Hawthorne found he could not “but partake of the ferment around him.”

Finally, in November 1841, Hawthorne left Brook Farm for good; and in October of the next year, he resigned as an Associate of the Brook Farm Institute of Agriculture and Education (suing to recover his initial investment). Now quit of the cows and the manure piles (which he referred to as “the gold mine” in his letters to Sophia), Hawthorne got married in Boston on July 9, 1842, settled into a happy and ordered domesticity in the Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts, and began composing the tales and sketches that would be collected in Mosses from an Old Manse (1846). There, in the antiquated “Manse” built in 1765 by the grandfather of his Concord neighbor, Ralph Waldo Emeison—and not among the communitarians along the Charles River—Hawthorne at last found the undisturbed opportunity, as he confided to his notebook, “to take pen in hand.”

The man who composed the romance of Blithedale still retained friendships with many of those earlier associated with Brook Farm. And he still required a quiet, secluded environment in which to work. But the Nathaniel Hawthorne who now lived with his wife and three children in a rented cottage in West Newton, Massachusetts, enjoyed a substantial literary reputation, both in England and in the United States. If he could not boast of riches from his work, his wife at least could boast of accolades. In a letter to her sister-in-law, she proudly noted that the great English poet Robert Browning considered Hawthorne “the finest genius that has appeared in English literature for many years.”

In keeping with its author’s reputation, contemporary reviews of The Blithedale Romance hailed it as the work of a man of unquestioned literary genius. “Unmistakably the finest production of genius in either hemisphere, for this quarter at least,” sang a notice in England’s Westminster Review (probably written by the English novelist George Eliot).

Not surprisingly, on both sides of the Atlantic, reviewers seized upon the book’s Brook Farm associations and connected these with the fact that The Blithedale Romance was the first of Hawthorne’s longer fictions to employ a first-person narrator. The conclusion repeatedly drawn from these observations was that the romance of 1852 offered itself as a barely disguised autobiographical account of the author’s brief sojourn at Brook Farm and, with that, Hawthorne’s final judgment on the experiment itself. “Certainly,” argued the reviewer for the Christian Examiner, “one has reason to believe that Mr. Hawthorne is presenting in these pages a story, which ... is essentially a delineation of life and character as presented at ‘Brook Farm.’ ”

In support of these views, the book reviewers of 1852—and literary critics ever since—pointed to parallels between Hawthorne’s characters and various individuals linked with Brook Farm. The drowned Zenobia was identified with the women’s rights advocate Margaret Fuller, who had herself drowned in a shipwreck just two years before. Hollingsworth was said to resemble the lecturer and social reformer Orestes Brownson or George Ripley, Brook Farm’s founder. And Miles Coverdale, the first-person narrator, was taken as a projection of the author, voicing the attitudes through which “Mr. Hawthorne would endeavor covertly to show the futility of the enterprise in whose favor he was once enlisted.” Those who read the story through a grid of real-world antecedents thus tended to see the whole as an unmediated indictment of socialism and proof, as one English reviewer phrased it, that “Mr. Hawthorne is not a disciple of that school of human perfectibility which has given rise to plans of pantisocracy and similar Arcadias.”

But there were also those who cautioned against so narrowly autobiographical a reading. Orestes Brownson, who had known many of the Brook Farm participants and sent his son there for schooling, reviewed The Blithedale Romance as a story “connected with some of our personal friends.” Yet he ended by advising readers that “very little of the actual persons engaged in it, or of the actual goings-on at Brook Farm” were to be found in its pages. Similarly, while some reviewers persisted in seeing Miles Coverdale as at least “a partial presentment of the author’s own person,” others followed the view of Edwin Percy Whipple, who treated Coverdale as just another invented character. Writing for Graham’s Magazine in September 1852, Whipple emphasized the ambiguous nature of this narrator, pointing out that as we read the novel, we become joint watchers with Miles himself, and sometimes find ourselves disagreeing with him in his interpretation of an act or expression of the persons he is observing.”

Of course, more was at stake in these debates than simply the proper reading of the latest Hawthorne fiction. Depending on a reviewer’s own ideological commitments, it could matter a great deal whether the reigning master of American romance intended to satirize socialism or altogether condemn efforts at societal improvement. These were, after all, the abiding concerns of the two decades preceding the Civil War—decades that saw a proliferation of experimental socialist communities and increasingly organized public activism directed at correcting a host of perceived social ills.

The great financial Panic of 1837 had shut banks, closed off credit, and caused many smaller farmers to lose their holdings. In the ensuing depression, which lasted into the 1840s, thousands of acres in Hawthorne’s native New England were abandoned or were sold off as summer resorts to wealthy industrialists from Boston and New York. A newly dispossessed rural population moved into the cities and factory towns, joining there with recently arrived European immigrants to form an underclass of urban poor. By the 1840s, the sight of small children begging on the streets of major urban centers was no longer unusual. At the same time, a rapidly developing industrialization made possible by a technology forged of steam and iron was changing the face of what had formerly been a self-consciously agrarian nation. While the bulk of the population remained on the land, by the 1840s there was a demonstrable centripetal movement toward the town, the city, and the factory. Although the image had largely been an illusion, the nation’s image of itself as a land of independent yeoman farmers was quickly being eroded by the reality of a ruthless market economy and the exploitation of wage laborers in the cities and factory towns.

In response, Americans were gripped by a wave of antiurbanism that lasted until the eve of the Civil War. The unprecedented accumulation of capital in the hands of a powerful few, the new technology, city tenements, overcrowded factory towns, and callous public institutions were all blamed as the causes of urban poverty, increased crime, and general moral decay. Private societies and philanthropic organizations sprang up to attempt the rehabilitation of criminals, the protection of prostitutes, and the care of orphans and paupers—though no group had resources adequate to the task. Those who despaired of such ameliorative measures took upon themselves more ambitious tasks for the reformation of society. All across the country, independent communities—generally organized around agriculture rather than manufacturing—were formed according

to various idealistic blueprints for social and economic harmony. Brook Farm was only one such experiment.

Adding to—indeed, probably central to—the feverish political pitch of the antebellum decades was the increasing agitation on behalf of the country’s two largest disenfranchised groups: blacks and women. The first women’s rights convention was held at Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. And, in a last-ditch effort to placate southern secessionists, Congress passed the notorious Compromise of 1850, with its more severe fugitive slave act. Increasingly, antislavery activists and women’s rights advocates made common cause, demanding that the nation live up to its democratic pretensions.

The other great public debate to which Hawthorne only glancingly alludes was the Indian Question. Ever since the forcible removal of the Cherokee from their lands in Georgia in 1838, just three years before Hawthorne joined the Brook Farm community, government mistreatment of the Indians had repeatedly elicited protests from many of Hawthorne’s friends and acquaintances, including Emerson and Margaret Fuller. Within the novel, the disappearance of Indian presence is first replicated symbolically when the Blithedalers form a committee to choose a name for the fledgling community. But the result is the erasure of “the old Indian name of the premises” because “it chanced to be a harsh, ill-connected, and interminable word.” A second reference attaches to the rock known as “Eliot’s pulpit.” By tradition, this is the place where, two hundred years earlier, the Puritan minister John Eliot had preached to members of the local Narragansett tribe in their own tongue. By the time the Blithedale foursome visits Eliot’s pulpit, however, the area remains still “a wild tract of woodland,” but no wigwams, no Indian “posterity” are any longer in sight. In both instances, Hawthorne appears to subscribe to the popular (but erroneous) nineteenth-century trope of the Vanishing Indian.

The Scarlet Letter

The Scarlet Letter Young Goodman Brown : By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated

Young Goodman Brown : By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated The Birthmark

The Birthmark The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 1

The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 1 The Minister's Black Veil

The Minister's Black Veil The Great Stone Face, and Other Tales of the White Mountains

The Great Stone Face, and Other Tales of the White Mountains The House of the Seven Gables

The House of the Seven Gables The Snow Image

The Snow Image The Blithedale Romance

The Blithedale Romance Rappaccini's Daughter: By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated

Rappaccini's Daughter: By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated Twice-Told Tales

Twice-Told Tales Twice Told Tales

Twice Told Tales The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 2

The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 2_preview.jpg) Footprints on the Sea-Shore (From Twice Told Tales)

Footprints on the Sea-Shore (From Twice Told Tales) Main Street

Main Street_preview.jpg) The Seven Vagabonds (From Twice Told Tales)

The Seven Vagabonds (From Twice Told Tales) Fanshawe

Fanshawe Chippings with a Chisel

Chippings with a Chisel Selected Tales and Sketches

Selected Tales and Sketches Young Goodman Brown

Young Goodman Brown Roger Malvin's Burial

Roger Malvin's Burial The Prophetic Pictures

The Prophetic Pictures The Village Uncle

The Village Uncle Scarlet Letter (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Scarlet Letter (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Procession of Life

The Procession of Life Drowne's Wooden Image

Drowne's Wooden Image Hawthorne's Short Stories

Hawthorne's Short Stories My Kinsman, Major Molineux

My Kinsman, Major Molineux Legends of the Province House

Legends of the Province House Foot-Prints on the Sea-Shore

Foot-Prints on the Sea-Shore The Haunted Quack

The Haunted Quack Tanglewood Tales

Tanglewood Tales The Seven Vagabonds

The Seven Vagabonds Mosses from an Old Manse, Volume 2

Mosses from an Old Manse, Volume 2 The Canterbury Pilgrims

The Canterbury Pilgrims Wakefield

Wakefield The Gray Champion

The Gray Champion The White Old Maid

The White Old Maid The Snow-Image: A Childish Miracle

The Snow-Image: A Childish Miracle The Gentle Boy

The Gentle Boy Mr. Higginbotham's Catastrophe

Mr. Higginbotham's Catastrophe![The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/the_threefold_destiny_a_fairy_legend_by_ashley_allen_royce_pseud__preview.jpg) The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.]

The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.] Lady Eleanore`s Mantle

Lady Eleanore`s Mantle The Great Carbuncle

The Great Carbuncle The Portable Hawthorne (Penguin Classics)

The Portable Hawthorne (Penguin Classics) True Stories from History and Biography

True Stories from History and Biography