- Home

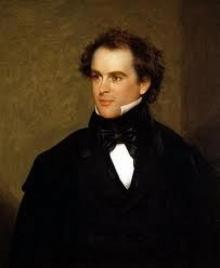

- Nathaniel Hawthorne

The Seven Vagabonds (From Twice Told Tales)

The Seven Vagabonds (From Twice Told Tales) Read online

Produced by David Widger. HTML version by Al Haines.

TWICE TOLD TALES

THE SEVEN VAGABONDS

By Nathaniel Hawthorne

Rambling on foot in the spring of my life and the summer of the year,I came one afternoon to a point which gave me the choice of threedirections. Straight before me, the main road extended its dustylength to Boston; on the left a branch went towards the sea, and wouldhave lengthened my journey a trifle of twenty or thirty miles; whileby the right-hand path, I might have gone over hills and lakes toCanada, visiting in my way the celebrated town of Stamford. On alevel spot of grass, at the foot of the guidepost, appeared an object,which, though locomotive on a different principle, reminded me ofGulliver's portable mansion among the Brobdignags. It was a hugecovered wagon, or, more properly, a small house on wheels, with a dooron one side and a window shaded by green blinds on the other. Twohorses, munching provender out of the baskets which muzzled them, werefastened near the vehicle: a delectable sound of music proceeded fromthe interior; and I immediately conjectured that this was someitinerant show, halting at the confluence of the roads to interceptsuch idle travellers as myself. A shower had long been climbing upthe western sky, and now hung so blackly over my onward path that itwas a point of wisdom to seek shelter here.

"Halloo! Who stands guard here? Is the doorkeeper asleep?" cried I,approaching a ladder of two or three steps which was let down from thewagon.

The music ceased at my summons, and there appeared at the door, notthe sort of figure that I had mentally assigned to the wanderingshowman, but a most respectable old personage, whom I was sorry tohave addressed in so free a style. He wore a snuff colored coat andsmall-clothes, with white-top boots, and exhibited the mild dignity ofaspect and manner which may often be noticed in aged schoolmasters,and sometimes in deacons, selectmen, or other potentates of that kind.A small piece of silver was my passport within his premises, where Ifound only one other person, hereafter to be described.

"This is a dull day for business," said the old gentleman, as heushered me in; "but I merely tarry here to refresh the cattle, beingbound for the camp-meeting at Stamford."

Perhaps the movable scene of this narrative is still peregrinating NewEngland, and may enable the reader to test the accuracy of mydescription. The spectacle--for I will not use the unworthy term ofpuppet-show--consisted of a multitude of little people assembled on aminiature stage. Among them were artisans of every kind, in theattitudes of their toil, and a group of fair ladies and gay gentlemenstanding ready for the dance; a company of foot-soldiers formed a lineacross the stage, looking stern, grim, and terrible enough, to make ita pleasant consideration that they were but three inches high; andconspicuous above the whole was seen a Merry-Andrew, in the pointedcap and motley coat of his profession. All the inhabitants of thismimic world were motionless, like the figures in a picture, or likethat people who one moment were alive in the midst of their businessand delights, and the next were transformed to statues, preserving aneternal semblance of labor that was ended, and pleasure that could befelt no more. Anon, however, the old gentleman turned the handle of abarrel-organ, the first note of which produced a most enliveningeffect upon the figures, and awoke them all to their properoccupations and amusements. By the self-same impulse the tailor pliedhis needle, the blacksmith's hammer descended upon the anvil, and thedancers whirled away on feathery tiptoes; the company of soldiersbroke into platoons, retreated from the stage, and were succeeded by atroop of horse, who came prancing onward with such a sound of trumpetsand trampling of hoofs, as might have startled Don Quixote himself;while an old toper, of inveterate ill habits, uplifted his blackbottle and took off a hearty swig. Meantime the Merry-Andrew began tocaper and turn somersets, shaking his sides, nodding his head, andwinking his eyes in as life-like a manner as if he were ridiculing thenonsense of all human affairs, and making fun of the whole multitudebeneath him. At length the old magician (for I compared the showmanto Prospero, entertaining his guests with a mask of shadows) pausedthat I might give utterance to my wonder.

"What an admirable piece of work is this!" exclaimed I, lifting up mybands in astonishment.

Indeed, I liked the spectacle, and was tickled with the old man'sgravity as he presided at it, for I had none of that foolish wisdomwhich reproves every occupation that is not useful in this world ofvanities. If there be a faculty which I possess more perfectly thanmost men, it is that of throwing myself mentally into situationsforeign to my own, and detecting, with a cheerful eye, the desirablecircumstances of each. I could have envied the life of thisgray-headed showman, spent as it had been in a course of safe andpleasurable adventure, in driving his huge vehicle sometimes throughthe sands of Cape Cod, and sometimes over the rough forest roads ofthe north and east, and halting now on the green before a villagemeeting-house, and now in a paved square of the metropolis. How oftenmust his heart have been gladdened by the delight of children, as theyviewed these animated figures! or his pride indulged, by haranguinglearnedly to grown men on the mechanical powers which produced suchwonderful effects! or his gallantry brought into play (for this is anattribute which such grave men do not lack) by the visits of prettymaidens! And then with how fresh a feeling must he return, atintervals, to his own peculiar home!

"I would I were assured of as happy a life as his," thought I. Thoughthe showman's wagon might have accommodated fifteen or twentyspectators, it now contained only himself and me, and a third personat whom I threw a glance on entering. He was a neat and trim youngman of two or three and twenty; his drab hat, and green frock-coatwith velvet collar, were smart, though no longer new; while a pair ofgreen spectacles, that seemed needless to his brisk little eyes, gavehim something of a scholar-like and literary air. After allowing me asufficient time to inspect the puppets, he advanced with a bow, anddrew my attention to some books in a corner of the wagon. These heforthwith began to extol, with an amazing volubility of well-soundingwords, and an ingenuity of praise that won him my heart, as beingmyself one of the most merciful of critics. Indeed, his stockrequired some considerable powers of commendation in the salesman;there were several ancient friends of mine, the novels of those happydays when my affections wavered between the Scottish Chiefs and ThomasThumb; besides a few of later date, whose merits had not beenacknowledged by the public. I was glad to find that dear littlevenerable volume, the New England Primer, looking as antique as ever,though in its thousandth new edition; a bundle of superannuated giltpicture-books made such a child of me, that, partly for the glitteringcovers, and partly for the fairy-tales within, I bought the whole; andan assortment of ballads and popular theatrical songs drew largely onmy purse. To balance these expenditures, I meddled neither withsermons, nor science, nor morality, though volumes of each were there;nor with a Life of Franklin in the coarsest of paper, but so showilybound that it was emblematical of the Doctor himself, in the courtdress which he refused to wear at Paris; nor with Webster's SpellingBook, nor some of Byron's minor poems, nor half a dozen littleTestaments at twenty-five cents each.

Thus far the collection might have been swept from some greatbookstore, or picked up at an evening auction-room; but there was onesmall blue-covered pamphlet, which the peddler handed me with sopeculiar an air, that I purchased it immediately at his own price; andthen, for the first time, the thought struck me, that I had spokenface to face with the veritable author of a printed book. Theliterary man now evinced a great kindness for me, and I ventured toinquire which way he was travelling.

"O," said he, "I keep company with this old gentleman here, and we aremovin

g now towards the camp-meeting at Stamford!"

He then explained to me, that for the present season he had rented acorner of the wagon as a bookstore, which, as he wittily observed, wasa true Circulating Library, since there were few parts of the countrywhere it had not gone its rounds. I approved of the plan exceedingly,and began to sum up within my mind the many uncommon felicities in thelife of a book-peddler, especially when his character resembled that ofthe individual before me. At a high rate was to be reckoned the dailyand hourly enjoyment of such interviews as the present, in which heseized upon the admiration of a passing stranger, and made him awarethat a man of literary taste, and even of literary achievement, wastravelling the country in a showman's wagon. A more valuable, yet notinfrequent triumph, might be won in his conversation with some elderlyclergyman, long vegetating in a rocky, woody, watery back settlement ofNew England, who, as he recruited

The Scarlet Letter

The Scarlet Letter Young Goodman Brown : By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated

Young Goodman Brown : By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated The Birthmark

The Birthmark The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 1

The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 1 The Minister's Black Veil

The Minister's Black Veil The Great Stone Face, and Other Tales of the White Mountains

The Great Stone Face, and Other Tales of the White Mountains The House of the Seven Gables

The House of the Seven Gables The Snow Image

The Snow Image The Blithedale Romance

The Blithedale Romance Rappaccini's Daughter: By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated

Rappaccini's Daughter: By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated Twice-Told Tales

Twice-Told Tales Twice Told Tales

Twice Told Tales The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 2

The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 2_preview.jpg) Footprints on the Sea-Shore (From Twice Told Tales)

Footprints on the Sea-Shore (From Twice Told Tales) Main Street

Main Street_preview.jpg) The Seven Vagabonds (From Twice Told Tales)

The Seven Vagabonds (From Twice Told Tales) Fanshawe

Fanshawe Chippings with a Chisel

Chippings with a Chisel Selected Tales and Sketches

Selected Tales and Sketches Young Goodman Brown

Young Goodman Brown Roger Malvin's Burial

Roger Malvin's Burial The Prophetic Pictures

The Prophetic Pictures The Village Uncle

The Village Uncle Scarlet Letter (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Scarlet Letter (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Procession of Life

The Procession of Life Drowne's Wooden Image

Drowne's Wooden Image Hawthorne's Short Stories

Hawthorne's Short Stories My Kinsman, Major Molineux

My Kinsman, Major Molineux Legends of the Province House

Legends of the Province House Foot-Prints on the Sea-Shore

Foot-Prints on the Sea-Shore The Haunted Quack

The Haunted Quack Tanglewood Tales

Tanglewood Tales The Seven Vagabonds

The Seven Vagabonds Mosses from an Old Manse, Volume 2

Mosses from an Old Manse, Volume 2 The Canterbury Pilgrims

The Canterbury Pilgrims Wakefield

Wakefield The Gray Champion

The Gray Champion The White Old Maid

The White Old Maid The Snow-Image: A Childish Miracle

The Snow-Image: A Childish Miracle The Gentle Boy

The Gentle Boy Mr. Higginbotham's Catastrophe

Mr. Higginbotham's Catastrophe![The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/the_threefold_destiny_a_fairy_legend_by_ashley_allen_royce_pseud__preview.jpg) The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.]

The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.] Lady Eleanore`s Mantle

Lady Eleanore`s Mantle The Great Carbuncle

The Great Carbuncle The Portable Hawthorne (Penguin Classics)

The Portable Hawthorne (Penguin Classics) True Stories from History and Biography

True Stories from History and Biography