- Home

- Nathaniel Hawthorne

Selected Tales and Sketches Page 5

Selected Tales and Sketches Read online

Page 5

The Scarlet Letter seems once to have been intended for inclusion in a collection to be titled “Old-Time Legends; together with sketches, experimental and ideal.” But then, of course, “The Custom-House” came along to help it stand alone. Subsequently, The Snow-Image (1851) gathered up the four tales Hawthorne had produced in 1849 and 1850; but as the volume is filled out with a much larger number of earlier pieces hitherto uncollected, the whole seems more a publishing convenience than a literary, project. And the second edition of the Mosses (1854) continues this same activity of universal self-collection-largely at the urging of now eager editors, and at some prejudice to the anti-transcendental unity of that remarkable work. By that date, of course, Hawthorne was the accomplished author of his “Three American Romances” and, searching in England for the theme of yet another extended romantic fiction, he was proportionately less concerned about the significance of his “obscure” years.

Of the post-1846 tales, several were solicited by friendly magazine editors. At least one, “The Snow-Image” (1850), was explicitly designated a “childish” performance; and it may be that “The Great Stone Face” (1850) was also meant to reach Hawthorne’s secondary audience of youthful readers. An extended sketch called “Main-Street” (1849) reveals once again the full wickedness of Hawthorne’s mature historical irony, but it reads best as a self-conscious defense of the earlier career as “moral” (rather than “positivistic”) historian of the Puritans; or else as a self-imposed review of the Puritan themes to be reactivated in The Scarlet Letter. And as it remains perfectly safe to regard “Ethan Brand” (1850) just as Hawthorne subtitled it, “A Chapter from an Abortive Romance,” so it seems fair to accept the 1846 Mosses as a sort of formal conclusion to Hawthorne’s career as writer and collector of tales and sketches. The novels were delayed, of course—in part, at least, by the second and more famous tour of custom-house service. But when they came, they came in a bunch. And in coming to constitute a sort of “Major Phase,” they have fully overshadowed the last, scattered attempts at short fiction.

Yet no survey of Hawthorne’s tales can afford to omit “Ethan Brand”—not only because it may signal Hawthorne’s first, unsuccessful transition from tale to romance, but also, and more significantly, because it makes clear, one last time, that Hawthorne’s most romantic imaginings are never quite free of historical source and local application. One powerful reason for believing “Ethan Brand” indeed survives as but a fragment of a longer work is that it draws on and virtually exausts the wealth of particular observation Hawthorne had set down in a 50,000-word notebook of his 1838 trip to western Massachusetts: bad policy, if one brief tale were all he had originally intended. But the best reason for valuing the actual achievement of “Ethan Brand” is that in it all this “local color” is deployed in the career of an American Faust who has never ceased to be a Puritan, if only malgré lui.

When we ask, as we must, what it means for Ethan Brand to have begun his notorious search for the “unpardonable sin” in a spirit not of arrogance but of brotherhood, the answer keeps coming back that—like Melville’s Ahab, whose creation he plainly helped to inspire—Brand has hoped to act as a sort of representative human hero, a kind of latter-day, backwoods New England Prometheus. Fire having already been snatched from the jealous gods, and long since harnessed to the civilized arts of environmental engineering, what daring task remained? Or else, more defiantly formulated, what secret remained, within the fire, to remind the brooding humanist of the awful uncertainty that still enshrouded human life? Not death, apparently, but only the knowledge of that one supposed sin which of its very nature defied the mercy of even a thoroughly encovenanted Jehova. Perhaps the secret was not entirely past finding out.

No doubt the question was, in itself, impious in the last degree, like Ahab’s monomaniac inquisition into the mystery of universal iniquity. No doubt Brand looked “too long into the fire.” So that the fiery conclusion—of suicide at the moment of cosmic blasphemy—may seem predictable enough. Yet the sense of triumph over all the world’s “half-way” sinners is one that would have to develop. Himself, at last, a “Brand [Un]Plucked from the Burning,” still this ultimate neopuritan rebel appears to have begun with a concern for the reason of human despair as plausible as that of Cotton Mather himself. Nor, as the insistent allusions to writers of the Enlightenment and of Romanticism make clear, had the matter of malignity been entirely settled or left behind; from which observation, we may infer, the author of Moby-Dick took considerable aid and comfort.

If Hawthorne’s own effort proved “abortive,” the explanation must surely lie in some temperamental inability to sustain a Melvillean protest against the enduring legacy of Calvinist orthodoxy. More historical than speculative, finally, Hawthorne’s circumspect intelligence could see at once that the transcendence promised by perfect negation was as illusory as any other: one denied what one knew, then lapsed to the elements of universal process. Others endured, if not to tell the tale, at least to gather up the fragments.

Appropriately, therefore, The Scarlet Letter—the first and most compelling of the longer fictions—would return to the world whose moral shape Hawthorne knew best, the world of the Puritans as it functioned in the second decade of John Winthrop’s model “City on a Hill.” The laws of this would-be Utopia are strict, but they are known; and sinners must bear the burden of social cause and effect. No one need wish, as Hawthorne makes clear in “Main-Street,” to repeat the lives of ancestors whom experience had taught so much “amiss”: Winthrop’s vaunted “liberty” seemed more “like an iron cage,” and its “rigidity” appears to have generated even further “distortions of the moral nature.” Yet the tale might still be retold, if only to illustrate the moral premise of historicism as such: even the most repressive ideologies had seemed like a good idea at the time; and no “self” entirely escapes the limits of its correlative world.

Not even the artist escapes. His domain might be divided between past and present, inner and outer. But gestures of ultimacy remained empty. His subject could be only his own world-in-process. And America was no exception.

A Note on the Text

All the texts printed here are those established by the Centenary Edition of Hawthorne’s Works (Columbus: Ohio State University Press): Twice-told Tales (IX, 1974); Mosses from an Old Manse (X, 1974); The Snow-Image and Uncollected Tales (XI, 1974); and the forthcoming Miscellany. The sequence of printing, however, reflects the order of their first magazine or gift-book appearance. With two exceptions: “The Notch of the White Mountains” (Nov., 1835) appears as introductory to “The Ambitious Guest” (June, 1835); and “The Christmas Banquet” (Jan., 1844) is placed as immediate sequel to “Egotism ; or, The Bosom-Serpent” (Mar., 1843).

The Hollow of the Three Hills

IN those strange old times, when fantastic dreams and mad-men’s reveries were realized among the actual circumstances of life, two persons met together at an appointed hour and place. One was a lady, graceful in form and fair of feature, though pale and troubled, and smitten with an untimely blight in what should have been the fullest bloom of her years; the other was an ancient and meanly dressed woman, of ill-favored aspect, and so withered, shrunken and decrepit, that even the space since she began to decay must have exceeded the ordinary term of human existence. In the spot where they encountered, no mortal could observe them. Three little hills stood near each other, and down in the midst of them sunk a hollow basin, almost mathematically circular, two or three hundred feet in breadth, and of such depth that a stately cedar might but just be visible above the sides. Dwarf pines were numerous upon the hills, and partly fringed the outer verge of the intermediate hollow; within which there was nothing but the brown grass of October, and here and there a tree-trunk, that had fallen long ago, and lay mouldering with no green successor from its roots. One of these masses of decaying wood, formerly a majestic oak, rested close beside a pool of green and sluggish water at the bottom of the basin. Such scene

s as this (so gray tradition tells) were once the resort of a Power of Evil and his plighted subjects; and here, at midnight or on the dim verge of evening, they were said to stand round the mantling pool, disturbing its putrid waters in the performance of an impious baptismal rite. The chill beauty of an autumnal sunset was now gilding the three hill-tops, whence a paler tint stole down their sides into the hollow.

“Here is our pleasant meeting come to pass,” said the aged crone, “according as thou hast desired. Say quickly what thou wouldst have of me, for there is but a short hour that we may tarry here.”

As the old withered woman spoke, a smile glimmered on her countenance, like lamplight on the wall of a sepulchre. The lady trembled, and cast her eyes upward to the verge of the basin, as if meditating to return with her purpose unaccomplished. But it was not so ordained.

“I am stranger in this land, as you know,” said she at length. “Whence I come it matters not;—but I have left those behind me with whom my fate was intimately bound, and from whom I am cut off forever. There is a weight in my bosom that I cannot away with, and I have come hither to inquire of their welfare. ”

“And who is there by this green pool, that can bring thee news from the ends of the Earth?” cried the old woman, peering into the lady’s face. “Not from my lips mayst thou hear these tidings; yet, be thou bold, and the daylight shall not pass away from yonder hill-top, before thy wish be granted.”

“I will do your bidding though I die,” replied the lady desperately.

The old woman seated herself on the trunk of the fallen tree, threw aside the hood that shrouded her gray locks, and beckoned her companion to draw near.

“Kneel down,” she said, “and lay your forehead on my knees. ”

She hesitated a moment, but the anxiety, that had long been kindling, burned fiercely up within her. As she knelt down, the border of her garment was dipped into the pool; she laid her forehead on the old woman’s knees, and the latter drew a cloak about the lady’s face, so that she was in darkness. Then she heard the muttered words of a prayer, in the midst of which she started, and would have arisen.

“Let me flee,—let me flee and hide myself, that they may not look upon me!” she cried. But, with returning recollection, she hushed herself, and was still as death.

For it seemed as if other voices—familiar in infancy, and unforgotten through many wanderings, and in all the vicissitudes of her heart and fortune—were mingling with the accents of the prayer. At first the words were faint and indistinct, not rendered so by distance, but rather resembling the dim pages of a book, which we strive to read by an imperfect and gradually brightening light. In such a manner, as the prayer proceeded, did those voices strengthen upon the ear; till at length the petition ended, and the conversation of an aged man, and of a woman broken and decayed like himself, became distinctly audible to the lady as she knelt. But those strangers appeared not to stand in the hollow depth between the three hills. Their voices were encompassed and re-echoed by the walls of a chamber, the windows of which were rattling in the breeze; the regular vibration of a clock, the crackling of a fire, and the tinkling of the embers as they fell among the ashes, rendered the scene almost as vivid as if painted to the eye. By a melancholy hearth sat these two old people, the man calmly despondent, the woman querulous and tearful, and their words were all of sorrow. They spoke of a daughter, a wanderer they knew not where, bearing dishonor along with her, and leaving shame and affliction to bring their gray heads to the grave. They alluded also to other and more recent woe, but in the midst of their talk, their voices seemed to melt into the sound of the wind sweeping mournfully among the autumn leaves; and when the lady lifted her eyes, there was she kneeling in the hollow between three hills.

“A weary and lonesome time yonder old couple have of it,” remarked the old woman, smiling in the lady’s face.

“And did you also hear them!” exclaimed she, a sense of intolerable humiliation triumphing over her agony and fear.

“Yea; and we have yet more to hear,” replied the old woman. “Wherefore, cover thy face quickly.”

Again the withered hag poured forth the monotonous words of a prayer that was not meant to be acceptable in Heaven; and soon, in the pauses of her breath, strange murmurings began to thicken, gradually increasing so as to drown and overpower the charm by which they grew. Shrieks pierced through the obscurity of sound, and were succeeded by the singing of sweet female voices, which in their turn gave way to a wild roar of laughter, broken suddenly by groanings and sobs, forming altogether a ghastly confusion of terror and mourning and mirth. Chains were rattling, fierce and stern voices uttered threats, and the scourge resounded at their command. All these noises deepened and became substantial to the listener’s ear, till she could distinguish every soft and dreamy accent of the love songs, that died causelessly into funeral hymns. She shuddered at the unprovoked wrath which blazed up like the spontaneous kindling of flame, and she grew faint at the fearful merriment, raging miserably around her. In the midst of this wild scene, where unbound passions jostled each other in a drunken career, there was one solemn voice of a man, and a manly and melodious voice it might once have been. He went to-and-fro continually, and his feet sounded upon the floor. In each member of that frenzied company, whose own burning thoughts had become their exclusive world, he sought an auditor for the story of his individual wrong, and interpreted their laughter and tears as his reward of scorn or pity. He spoke of woman’s perfidy, of a wife who had broken her holiest vows, of a home and heart made desolate. Even as he went on, the shout, the laugh, the shriek, the sob, rose up in unison, till they changed into the hollow, fitful, and uneven sound of the wind, as it fought among the pine-trees on those three lonely hills. The lady looked up, and there was the withered woman smiling in her face.

“Couldst thou have thought there were such merry times in a Mad House?” inquired the latter.

“True, true,” said the lady to herself; “there is mirth within its walls, but misery, misery without.”

“Wouldst thou hear more?” demanded the old woman.

“There is one other voice I would fain listen to again,” replied the lady faintly.

“Then lay down thy head speedily upon my knees, that thou may‘st get thee hence before the hour be past.”

The golden skirts of day were yet lingering upon the hills, but deep shades obscured the hollow and the pool, as if sombre night were rising thence to overspread the world. Again that evil woman began to weave her spell. Long did it proceed unanswered, till the knolling of a bell stole in among the intervals of her words, like a clang that had travelled far over valley and rising ground, and was just ready to die in the air. The lady shook upon her companion’s knees, as she heard that boding sound. Stronger it grew and sadder, and deepened into the tone of a death-bell, knolling dolefully from some ivy-mantled tower, and bearing tidings of mortality and woe to the cottage, to the hall, and to the solitary wayfarer, that all might weep for the doom appointed in turn to them. Then came a measured tread, passing slowly, slowly on, as of mourners with a coffin, their garments trailing on the ground, so that the ear could measure the length of their melancholy array. Before them went the priest, reading the burial-service, while the leaves of his book were rustling in the breeze. And though no voice but his was heard to speak aloud, still there were revilings and anathemas, whispered but distinct, from women and from men, breathed against the daughter who had wrung the aged hearts of her parents,—the wife who had betrayed the trusting fondness of her husband,—the mother who had sinned against natural affection, and left her child to die. The sweeping sound of the funeral train faded away like a thin vapour, and the wind, that just before had seemed to shake the coffin-pall, moaned sadly round the verge of the Hollow between three Hills. But when the old woman stirred the kneeling lady, she lifted not her head.

“Here has been a sweet hour’s sport!” said the withered crone, chuckling to herself.

Sir William Phi

ps

Few of the personages of past times (except such as have gained renown in fire-side legends as well as in written history) are anything more than mere names to their successors. They seldom stand up in our Imaginations like men. The knowledge, communicated by the historian and biographer, is analogous to that which we acquire of a country by the map,—minute, perhaps, and accurate, and available for all necessary purposes,—but cold and naked, and wholly destitute of the mimic charm produced by landscape painting. These defects are partly remediable, and even without an absolute violation of literal truth, although by methods rightfully interdicted to professors of biographical exactness. A license must be assumed in brightening the materials which time has rusted, and in tracing out the half-obliterated inscriptions on the columns of antiquity; fancy must throw her reviving light on the faded incidents that indicate character, whence a ray will be reflected, more or less vividly, on the person to be described. The portrait of the ancient Governor, whose name stands at the head of this article, will owe any interest it may possess, not to his internal self, but to certain peculiarities of his fortune. These must be briefly noticed.

The birth and early life of Sir William Phips were rather an extraordinary prelude to his subsequent distinction. He was one of the twenty six children of a gun-smith, who exercised his trade—where hunting and war must have given it a full encouragement—in a small frontier settlement near the mouth of the river Keunebec. Within the boundaries of the Puritan provinces, and wherever those governments extended an effectual sway, no depth nor solitude of the wilderness could exclude youth from all the common opportunities of moral, and far more than common ones of religious education. Each settlement of the Pilgrims was a little piece of the old world, inserted into the new,—it was like Gideon’s fleece, unwet with dew,—the desert wind, that breathed over it, left none of its wild influences there. But the first settlers of Maine and New-Hampshire were led thither entirely by carnal motives; their governments were feeble, uncertain, sometimes nominally annexed to their sister colonies, and sometimes asserting a troubled independence; their rulers might be deemed, in more than one instance, lawless adventurers, who found that security in the forest which they had forfeited in Europe. Their clergy (unlike that revered band who acquired so singular a fame elsewhere in New-England) were too often destitute of the religious fervor which should have kept them in the track of virtue, unaided by the restraints of human law and the dread of worldly dishonor; and there are records of lamentable lapses on the part of those holy men, which, if we may argue the disorder of the sheep from the unfitness of the shepherd, tell a sad tale as to the morality of the eastern provinces. In this state of society the future governor grew up, and many years after, sailing with a fleet and an army to make war upon the French, he pointed out the very hills where he had reached the age of manhood, unskilled even to read and write. The contrast between the commencement and close of his life was the effect of casual circumstances. During a considerable time, he was a mariner, at a period when there was much license on the high seas. After attaining to some rank in the English navy, he heard of an ancient Spanish wreck off the coast of Hispaniola, of such mighty value, that, according to the stories of the day, the sunken gold might be seen to glisten and the diamonds to flash, as the triumphant billows tossed about their spoil. These treasures of the deep (by the aid of certain noblemen, who claimed the lion’s share) Sir William Phips sought for, and recovered, and was sufficiently enriched, even after an honest settlement with the partners of his adventure. That the land might give him honor, as the sea had given him wealth, he received knighthood from King James. Returning to New-England, he professed repentance of his sins, (of which, from the nature both of his early and more recent life, there could scarce fail to be some slight accumulation) was baptized, and, on the accession of the Prince of Orange to the throne, became the first governor under the second charter. And now, having arranged these preliminaries, we shall attempt to picture forth a day of Sir William’s life, introducing no very remarkable events, because history supplies us with none such, convertible to our purpose.

The Scarlet Letter

The Scarlet Letter Young Goodman Brown : By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated

Young Goodman Brown : By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated The Birthmark

The Birthmark The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 1

The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 1 The Minister's Black Veil

The Minister's Black Veil The Great Stone Face, and Other Tales of the White Mountains

The Great Stone Face, and Other Tales of the White Mountains The House of the Seven Gables

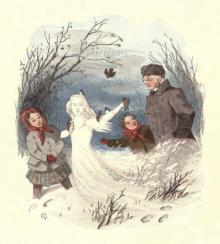

The House of the Seven Gables The Snow Image

The Snow Image The Blithedale Romance

The Blithedale Romance Rappaccini's Daughter: By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated

Rappaccini's Daughter: By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated Twice-Told Tales

Twice-Told Tales Twice Told Tales

Twice Told Tales The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 2

The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 2_preview.jpg) Footprints on the Sea-Shore (From Twice Told Tales)

Footprints on the Sea-Shore (From Twice Told Tales) Main Street

Main Street_preview.jpg) The Seven Vagabonds (From Twice Told Tales)

The Seven Vagabonds (From Twice Told Tales) Fanshawe

Fanshawe Chippings with a Chisel

Chippings with a Chisel Selected Tales and Sketches

Selected Tales and Sketches Young Goodman Brown

Young Goodman Brown Roger Malvin's Burial

Roger Malvin's Burial The Prophetic Pictures

The Prophetic Pictures The Village Uncle

The Village Uncle Scarlet Letter (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Scarlet Letter (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Procession of Life

The Procession of Life Drowne's Wooden Image

Drowne's Wooden Image Hawthorne's Short Stories

Hawthorne's Short Stories My Kinsman, Major Molineux

My Kinsman, Major Molineux Legends of the Province House

Legends of the Province House Foot-Prints on the Sea-Shore

Foot-Prints on the Sea-Shore The Haunted Quack

The Haunted Quack Tanglewood Tales

Tanglewood Tales The Seven Vagabonds

The Seven Vagabonds Mosses from an Old Manse, Volume 2

Mosses from an Old Manse, Volume 2 The Canterbury Pilgrims

The Canterbury Pilgrims Wakefield

Wakefield The Gray Champion

The Gray Champion The White Old Maid

The White Old Maid The Snow-Image: A Childish Miracle

The Snow-Image: A Childish Miracle The Gentle Boy

The Gentle Boy Mr. Higginbotham's Catastrophe

Mr. Higginbotham's Catastrophe![The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/the_threefold_destiny_a_fairy_legend_by_ashley_allen_royce_pseud__preview.jpg) The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.]

The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.] Lady Eleanore`s Mantle

Lady Eleanore`s Mantle The Great Carbuncle

The Great Carbuncle The Portable Hawthorne (Penguin Classics)

The Portable Hawthorne (Penguin Classics) True Stories from History and Biography

True Stories from History and Biography