- Home

- Nathaniel Hawthorne

Twice Told Tales Page 6

Twice Told Tales Read online

Page 6

THE GENTLE BOY.

In the course of the year 1656 several of the people calledQuakers--led, as they professed, by the inward movement of thespirit--made their appearance in New England. Their reputation asholders of mystic and pernicious principles having spread before them,the Puritans early endeavored to banish and to prevent the furtherintrusion of the rising sect. But the measures by which it wasintended to purge the land of heresy, though more than sufficientlyvigorous, were entirely unsuccessful. The Quakers, esteemingpersecution as a divine call to the post of danger, laid claim to aholy courage unknown to the Puritans themselves, who had shunned thecross by providing for the peaceable exercise of their religion in adistant wilderness. Though it was the singular fact that every nationof the earth rejected the wandering enthusiasts who practised peacetoward all men, the place of greatest uneasiness and peril, andtherefore in their eyes the most eligible, was the province ofMassachusetts Bay.

The fines, imprisonments and stripes liberally distributed by ourpious forefathers, the popular antipathy, so strong that it endurednearly a hundred years after actual persecution had ceased, wereattractions as powerful for the Quakers as peace, honor and rewardwould have been for the worldly-minded. Every European vessel broughtnew cargoes of the sect, eager to testify against the oppression whichthey hoped to share; and when shipmasters were restrained by heavyfines from affording them passage, they made long and circuitousjourneys through the Indian country, and appeared in the province asif conveyed by a supernatural power. Their enthusiasm, heightenedalmost to madness by the treatment which they received, producedactions contrary to the rules of decency as well as of rationalreligion, and presented a singular contrast to the calm and staiddeportment of their sectarian successors of the present day. Thecommand of the Spirit, inaudible except to the soul and not to becontroverted on grounds of human wisdom, was made a plea for mostindecorous exhibitions which, abstractedly considered, well deservedthe moderate chastisement of the rod. These extravagances, and thepersecution which was at once their cause and consequence, continuedto increase, till in the year 1659 the government of Massachusetts Bayindulged two members of the Quaker sect with the crown of martyrdom.

An indelible stain of blood is upon the hands of all who consented tothis act, but a large share of the awful responsibility must rest uponthe person then at the head of the government. He was a man of narrowmind and imperfect education, and his uncompromising bigotry was madehot and mischievous by violent and hasty passions; he exerted hisinfluence indecorously and unjustifiably to compass the death of theenthusiasts, and his whole conduct in respect to them was marked bybrutal cruelty. The Quakers, whose revengeful feelings were not lessdeep because they were inactive, remembered this man and hisassociates in after-times. The historian of the sect affirms that bythe wrath of Heaven a blight fell upon the land in the vicinity of the"bloody town" of Boston, so that no wheat would grow there; and hetakes his stand, as it were, among the graves of the ancientpersecutors, and triumphantly recounts the judgments that overtookthem in old age or at the parting-hour. He tells us that they diedsuddenly and violently and in madness, but nothing can exceed thebitter mockery with which he records the loathsome disease and "deathby rottenness" of the fierce and cruel governor.

* * * * *

On the evening of the autumn day that had witnessed the martyrdom oftwo men of the Quaker persuasion, a Puritan settler was returning fromthe metropolis to the neighboring country-town in which he resided.The air was cool, the sky clear, and the lingering twilight was madebrighter by the rays of a young moon which had now nearly reached theverge of the horizon. The traveller, a man of middle age, wrapped in agray frieze cloak, quickened his pace when he had reached theoutskirts of the town, for a gloomy extent of nearly four miles laybetween him and his home. The low straw-thatched houses were scatteredat considerable intervals along the road, and, the country having beensettled but about thirty years, the tracts of original forest stillbore no small proportion to the cultivated ground. The autumn windwandered among the branches, whirling away the leaves from all exceptthe pine trees and moaning as if it lamented the desolation of whichit was the instrument. The road had penetrated the mass of woods thatlay nearest to the town, and was just emerging into an open space,when the traveller's ears were saluted by a sound more mournful thaneven that of the wind. It was like the wailing of some one indistress, and it seemed to proceed from beneath a tall and lonely firtree in the centre of a cleared but unenclosed and uncultivated field.The Puritan could not but remember that this was the very spot whichhad been made accursed a few hours before by the execution of theQuakers, whose bodies had been thrown together into one hasty gravebeneath the tree on which they suffered. He struggled, however,against the superstitious fears which belonged to the age, andcompelled himself to pause and listen.

"The voice is most likely mortal, nor have I cause to tremble if it beotherwise," thought he, straining his eyes through the dim moonlight."Methinks it is like the wailing of a child--some infant, it may be,which has strayed from its mother and chanced upon this place ofdeath. For the ease of mine own conscience I must search this matterout." He therefore left the path and walked somewhat fearfully acrossthe field. Though now so desolate, its soil was pressed down andtrampled by the thousand footsteps of those who had witnessed thespectacle of that day, all of whom had now retired, leaving the deadto their loneliness.

The traveller at length reached the fir tree, which from the middleupward was covered with living branches, although a scaffold had beenerected beneath, and other preparations made for the work of death.Under this unhappy tree--which in after-times was believed to droppoison with its dew--sat the one solitary mourner for innocent blood.It was a slender and light-clad little boy who leaned his face upon ahillock of fresh-turned and half-frozen earth and wailed bitterly, yetin a suppressed tone, as if his grief might receive the punishment ofcrime. The Puritan, whose approach had been unperceived, laid his handupon the child's shoulder and addressed him compassionately.

"You have chosen a dreary lodging, my poor boy, and no wonder that youweep," said he. "But dry your eyes and tell me where your motherdwells; I promise you, if the journey be not too far, I will leave youin her arms tonight."

The boy had hushed his wailing at once, and turned his face upward tothe stranger. It was a pale, bright-eyed countenance, certainly notmore than six years old, but sorrow, fear and want had destroyed muchof its infantile expression. The Puritan, seeing the boy's frightenedgaze and feeling that he trembled under his hand, endeavored toreassure him:

"Nay, if I intended to do you harm, little lad, the readiest way wereto leave you here. What! you do not fear to sit beneath the gallows ona new-made grave, and yet you tremble at a friend's touch? Take heart,child, and tell me what is your name and where is your home."

"Friend," replied the little boy, in a sweet though faltering voice,"they call me Ilbrahim, and my home is here."

The pale, spiritual face, the eyes that seemed to mingle with themoonlight, the sweet, airy voice and the outlandish name almost madethe Puritan believe that the boy was in truth a being which had sprungup out of the grave on which he sat; but perceiving that theapparition stood the test of a short mental prayer, and rememberingthat the arm which he had touched was lifelike, he adopted a morerational supposition. "The poor child is stricken in his intellect,"thought he, "but verily his words are fearful in a place like this."He then spoke soothingly, intending to humor the boy's fantasy:

"Your home will scarce be comfortable, Ilbrahim, this cold autumnnight, and I fear you are ill-provided with food. I am hastening to awarm supper and bed; and if you will go with me, you shall sharethem."

"I thank thee, friend, but, though I be hungry and shivering withcold, thou wilt not give me food nor lodging," replied the boy, in thequiet tone which despair had taught him even so young. "My father wasof the people whom all men hate; they have laid him under this heap ofearth, and here is my home."

/>

The Puritan, who had laid hold of little Ilbrahim's hand, relinquishedit as if he were touching a loathsome reptile. But he possessed acompassionate heart which not even religious prejudice could hardeninto stone. "God forbid that I should leave this child to perish,though he comes of the accursed sect," said he to himself. "Do we notall spring from an evil root? Are we not all in darkness till thelight doth shine upon us? He shall not perish, neither in body nor, ifprayer and instruction may avail for him, in soul." He then spokealoud and kindly to Ilbrahim, who had again hid his face in the coldearth of the grave:

"Was every door in the land shut against you, my child, that you havewandered to this unhallowed spot?"

"They drove me forth from the prison when they took my father thence,"said the boy, "and I stood afar off watching the crowd of people; andwhen they were gone, I came hither, and found only this grave. I knewthat my father was sleeping here, and I said, 'This shall be myhome.'"

"No, child, no, not while I have a roof over my head or a morsel toshare with you," exclaimed the Puritan, whose sympathies were nowfully excited. "Rise up and come with me, and fear not any harm."

The boy wept afresh, and clung to the heap of earth as if the coldheart beneath it were warmer to him than any in a living breast. Thetraveller, however, continued to entreat him tenderly, and, seeming toacquire some degree of confidence, he at length arose; but his slenderlimbs tottered with weakness, his little head grew dizzy, and heleaned against the tree of death for support.

"My poor boy, are you so feeble?" said the Puritan. "When did youtaste food last?"

"I ate of bread and water with my father in the prison," repliedIlbrahim, "but they brought him none neither yesterday nor to-day,saying that he had eaten enough to bear him to his journey's end.Trouble not thyself for my hunger, kind friend, for I have lacked foodmany times ere now."

The traveller took the child in his arms and wrapped his cloak abouthim, while his heart stirred with shame and anger against thegratuitous cruelty of the instruments in this persecution. In theawakened warmth of his feelings he resolved that at whatever risk hewould not forsake the poor little defenceless being whom Heaven hadconfided to his care. With this determination he left the accursedfield and resumed the homeward path from which the wailing of the boyhad called him. The light and motionless burden scarcely impeded hisprogress, and he soon beheld the fire-rays from the windows of thecottage which he, a native of a distant clime, had built in theWestern wilderness. It was surrounded by a considerable extent ofcultivated ground, and the dwelling was situated in the nook of awood-covered hill, whither it seemed to have crept for protection.

"Look up, child," said the Puritan to Ilbrahim, whose faint head hadsunk upon his shoulder; "there is our home."

At the word "home" a thrill passed through the child's frame, but hecontinued silent. A few moments brought them to the cottage door, atwhich the owner knocked; for at that early period, when savages werewandering everywhere among the settlers, bolt and bar wereindispensable to the security of a dwelling. The summons was answeredby a bond-servant, a coarse-clad and dull-featured piece of humanity,who, after ascertaining that his master was the applicant, undid thedoor and held a flaring pine-knot torch to light him in. Farther backin the passageway the red blaze discovered a matronly woman, but nolittle crowd of children came bounding forth to greet their father'sreturn.

As the Puritan entered he thrust aside his cloak and displayedIlbrahim's face to the female.

"Dorothy, here is a little outcast whom Providence hath put into ourhands," observed he. "Be kind to him, even as if he were of those dearones who have departed from us."

"What pale and bright-eyed little boy is this, Tobias?" she inquired."Is he one whom the wilderness-folk have ravished from some Christianmother?"

"No, Dorothy; this poor child is no captive from the wilderness," hereplied. "The heathen savage would have given him to eat of his scantymorsel and to drink of his birchen cup, but Christian men, alas! hadcast him out to die." Then he told her how he had found him beneaththe gallows, upon his father's grave, and how his heart had promptedhim like the speaking of an inward voice to take the little outcasthome and be kind unto him. He acknowledged his resolution to feed andclothe him as if he were his own child, and to afford him theinstruction which should counteract the pernicious errors hithertoinstilled into his infant mind.

Dorothy was gifted with even a quicker tenderness than her husband,and she approved of all his doings and intentions.

"Have you a mother, dear child?" she inquired.

The tears burst forth from his full heart as he attempted to reply,but Dorothy at length understood that he had a mother, who like therest of her sect was a persecuted wanderer. She had been taken fromthe prison a short time before, carried into the uninhabitedwilderness and left to perish there by hunger or wild beasts. This wasno uncommon method of disposing of the Quakers, and they wereaccustomed to boast that the inhabitants of the desert were morehospitable to them than civilized man.

"Fear not, little boy; you shall not need a mother, and a kind one,"said Dorothy, when she had gathered this information. "Dry your tears,Ilbrahim, and be my child, as I will be your mother."

The good woman prepared the little bed from which her own children hadsuccessively been borne to another resting-place. Before Ilbrahimwould consent to occupy it he knelt down, and as Dorothy listed to hissimple and affecting prayer she marvelled how the parents that hadtaught it to him could have been judged worthy of death. When the boyhad fallen asleep, she bent over his pale and spiritual countenance,pressed a kiss upon his white brow, drew the bedclothes up about hisneck, and went away with a pensive gladness in her heart.

Tobias Pearson was not among the earliest emigrants from the oldcountry. He had remained in England during the first years of theCivil War, in which he had borne some share as a cornet of dragoonsunder Cromwell. But when the ambitious designs of his leader began todevelop themselves, he quitted the army of the Parliament and sought arefuge from the strife which was no longer holy among the people ofhis persuasion in the colony of Massachusetts. A more worldlyconsideration had perhaps an influence in drawing him thither, for NewEngland offered advantages to men of unprosperous fortunes as well asto dissatisfied religionists, and Pearson had hitherto found itdifficult to provide for a wife and increasing family. To thissupposed impurity of motive the more bigoted Puritans were inclined toimpute the removal by death of all the children for whose earthly goodthe father had been over-thoughtful. They had left their nativecountry blooming like roses, and like roses they had perished in aforeign soil. Those expounders of the ways of Providence, who had thusjudged their brother and attributed his domestic sorrows to his sin,were not more charitable when they saw him and Dorothy endeavoring tofill up the void in their hearts by the adoption of an infant of theaccursed sect. Nor did they fail to communicate their disapprobationto Tobias, but the latter in reply merely pointed at the little quiet,lovely boy, whose appearance and deportment were indeed as powerfularguments as could possibly have been adduced in his own favor. Evenhis beauty, however, and his winning manners sometimes produced aneffect ultimately unfavorable; for the bigots, when the outer surfacesof their iron hearts had been softened and again grew hard, affirmedthat no merely natural cause could have so worked upon them. Theirantipathy to the poor infant was also increased by the ill-success ofdivers theological discussions in which it was attempted to convincehim of the errors of his sect. Ilbrahim, it is true, was not a skilfulcontroversialist, but the feeling of his religion was strong asinstinct in him, and he could neither be enticed nor driven from thefaith which his father had died for.

The odium of this stubbornness was shared in a great measure by thechild's protectors, insomuch that Tobias and Dorothy very shortlybegan to experience a most bitter species of persecution in the coldregards of many a friend whom they had valued. The common peoplemanifested their opinions more openly. Pearson was a man of someconsideration, being a representative to the

General Court and anapproved lieutenant in the train-bands, yet within a week after hisadoption of Ilbrahim he had been both hissed and hooted. Once, also,when walking through a solitary piece of woods, he heard a loud voicefrom some invisible speaker, and it cried, "What shall be done to thebackslider? Lo! the scourge is knotted for him, even the whip of ninecords, and every cord three knots." These insults irritated Pearson'stemper for the moment; they entered also into his heart, and becameimperceptible but powerful workers toward an end which his most secretthought had not yet whispered.

* * * * *

On the second Sabbath after Ilbrahim became a member of their family,Pearson and his wife deemed it proper that he should appear with themat public worship. They had anticipated some opposition to thismeasure from the boy, but he prepared himself in silence, and at theappointed hour was clad in the new mourning-suit which Dorothy hadwrought for him. As the parish was then, and during many subsequentyears, unprovided with a bell, the signal for the commencement ofreligious exercises was the beat of a drum. At the first sound of thatmartial call to the place of holy and quiet thoughts Tobias andDorothy set forth, each holding a hand of little Ilbrahim, like twoparents linked together by the infant of their love. On their paththrough the leafless woods they were overtaken by many persons oftheir acquaintance, all of whom avoided them and passed by on theother side; but a severer trial awaited their constancy when they haddescended the hill and drew near the pine-built and undecorated houseof prayer. Around the door, from which the drummer still sent forthhis thundering summons, was drawn up a formidable phalanx, includingseveral of the oldest members of the congregation, many of themiddle-aged and nearly all the younger males. Pearson found itdifficult to sustain their united and disapproving gaze, but Dorothy,whose mind was differently circumstanced, merely drew the boy closerto her and faltered not in her approach. As they entered the door theyoverheard the muttered sentiments of the assemblage; and when thereviling voices of the little children smote Ilbrahim's ear, he wept.

The interior aspect of the meeting-house was rude. The low ceiling,the unplastered walls, the naked woodwork and the undraperied pulpitoffered nothing to excite the devotion which without such externalaids often remains latent in the heart. The floor of the building wasoccupied by rows of long cushionless benches, supplying the place ofpews, and the broad aisle formed a sexual division impassable exceptby children beneath a certain age.

Pearson and Dorothy separated at the door of the meeting-house, andIlbrahim, being within the years of infancy, was retained under thecare of the latter. The wrinkled beldams involved themselves in theirrusty cloaks as he passed by; even the mild-featured maidens seemed todread contamination; and many a stern old man arose and turned hisrepulsive and unheavenly countenance upon the gentle boy, as if thesanctuary were polluted by his presence. He was a sweet infant of theskies that had strayed away from his home, and all the inhabitants ofthis miserable world closed up their impure hearts against him, drewback their earth-soiled garments from his touch and said, "We areholier than thou."

Ilbrahim, seated by the side of his adopted mother and retaining fasthold of her hand, assumed a grave and decorous demeanor such as mightbefit a person of matured taste and understanding who should findhimself in a temple dedicated to some worship which he did notrecognize, but felt himself bound to respect. The exercises had notyet commenced, however, when the boy's attention was arrested by anevent apparently of trifling interest. A woman having her face muffledin a hood and a cloak drawn completely about her form advanced slowlyup the broad aisle and took place upon the foremost bench. Ilbrahim'sfaint color varied, his nerves fluttered; he was unable to turn hiseyes from the muffled female.

When the preliminary prayer and hymn were over, the minister arose,and, having turned the hour-glass which stood by the great Bible,commenced his discourse. He was now well stricken in years, a man ofpale, thin countenance, and his gray hairs were closely covered by ablack velvet skull-cap. In his younger days he had practically learnedthe meaning of persecution from Archbishop Laud, and he was not nowdisposed to forget the lesson against which he had murmured then.Introducing the often-discussed subject of the Quakers, he gave ahistory of that sect and a description of their tenets in which errorpredominated and prejudice distorted the aspect of what was true. Headverted to the recent measures in the province, and cautioned hishearers of weaker parts against calling in question the just severitywhich God-fearing magistrates had at length been compelled toexercise. He spoke of the danger of pity--in some cases a commendableand Christian virtue, but inapplicable to this pernicious sect. Heobserved that such was their devilish obstinacy in error that even thelittle children, the sucking babes, were hardened and desperateheretics. He affirmed that no man without Heaven's especial warrantshould attempt their conversion lest while he lent his hand to drawthem from the slough he should himself be precipitated into its lowestdepths.

The sands of the second hour were principally in the lower half of theglass when the sermon concluded. An approving murmur followed, and theclergyman, having given out a hymn, took his seat with muchself-congratulation, and endeavored to read the effect of hiseloquence in the visages of the people. But while voices from allparts of the house were tuning themselves to sing a scene occurredwhich, though not very unusual at that period in the province,happened to be without precedent in this parish.

The muffled female, who had hitherto sat motionless in the front rankof the audience, now arose and with slow, stately and unwavering stepascended the pulpit stairs. The quaverings of incipient harmony werehushed and the divine sat in speechless and almost terrifiedastonishment while she undid the door and stood up in the sacred deskfrom which his maledictions had just been thundered. She then divestedherself of the cloak and hood, and appeared in a most singular array.A shapeless robe of sackcloth was girded about her waist with aknotted cord; her raven hair fell down upon her shoulders, and itsblackness was defiled by pale streaks of ashes, which she had strewnupon her head. Her eyebrows, dark and strongly defined, added to thedeathly whiteness of a countenance which, emaciated with want and wildwith enthusiasm and strange sorrows, retained no trace of earlierbeauty. This figure stood gazing earnestly on the audience, and therewas no sound nor any movement except a faint shuddering which everyman observed in his neighbor, but was scarcely conscious of inhimself. At length, when her fit of inspiration came, she spoke forthe first few moments in a low voice and not invariably distinctutterance. Her discourse gave evidence of an imagination hopelesslyentangled with her reason; it was a vague and incomprehensiblerhapsody, which, however, seemed to spread its own atmosphere roundthe hearer's soul, and to move his feelings by some influenceunconnected with the words. As she proceeded beautiful but shadowyimages would sometimes be seen like bright things moving in a turbidriver, or a strong and singularly shaped idea leapt forth and seizedat once on the understanding or the heart. But the course of herunearthly eloquence soon led her to the persecutions of her sect, andfrom thence the step was short to her own peculiar sorrows. She wasnaturally a woman of mighty passions, and hatred and revenge nowwrapped themselves in the garb of piety. The character of her speechwas changed; her images became distinct though wild, and herdenunciations had an almost hellish bitterness.

"The governor and his mighty men," she said, "have gathered together,taking counsel among themselves and saying, 'What shall we do untothis people--even unto the people that have come into this land to putour iniquity to the blush?' And, lo! the devil entereth into thecouncil-chamber like a lame man of low stature and gravely apparelled,with a dark and twisted countenance and a bright, downcast eye. And hestandeth up among the rulers; yea, he goeth to and fro, whispering toeach; and every man lends his ear, for his word is 'Slay! Slay!' But Isay unto ye, Woe to them that slay! Woe to them that shed the blood ofsaints! Woe to them that have slain the husband and cast forth thechild, the tender infant, to wander homeless and hungry and cold tillhe die, and have saved the mother alive i

n the cruelty of their tendermercies! Woe to them in their lifetime! Cursed are they in the delightand pleasure of their hearts! Woe to them in their death-hour, whetherit come swiftly with blood and violence or after long and lingeringpain! Woe in the dark house, in the rottenness of the grave, when thechildren's children shall revile the ashes of the fathers! Woe, woe,woe, at the judgment, when all the persecuted and all the slain inthis bloody land, and the father, the mother and the child, shallawait them in a day that they cannot escape! Seed of the faith, seedof the faith, ye whose hearts are moving with a power that ye knownot, arise, wash your hands of this innocent blood! Lift your voices,chosen ones, cry aloud, and call down a woe and a judgment with me!"

Having thus given vent to the flood of malignity which she mistook forinspiration, the speaker was silent. Her voice was succeeded by thehysteric shrieks of several women, but the feelings of the audiencegenerally had not been drawn onward in the current with her own. Theyremained stupefied, stranded, as it were, in the midst of a torrentwhich deafened them by its roaring, but might not move them by itsviolence. The clergyman, who could not hitherto have ejected theusurper of his pulpit otherwise than by bodily force, now addressedher in the tone of just indignation and legitimate authority.

"Get you down, woman, from the holy place which you profane," he said,"Is it to the Lord's house that you come to pour forth the foulness ofyour heart and the inspiration of the devil? Get you down, andremember that the sentence of death is on you--yea, and shall beexecuted, were it but for this day's work."

"I go, friend, I go, for the voice hath had its utterance," repliedshe, in a depressed, and even mild, tone. "I have done my mission untothee and to thy people; reward me with stripes, imprisonment or death,as ye shall be permitted." The weakness of exhausted passion causedher steps to totter as she descended the pulpit stairs.

The people, in the mean while, were stirring to and fro on the floorof the house, whispering among themselves and glancing toward theintruder. Many of them now recognized her as the woman who hadassaulted the governor with frightful language as he passed by thewindow of her prison; they knew, also, that she was adjudged to sufferdeath, and had been preserved only by an involuntary banishment intothe wilderness. The new outrage by which she had provoked her fateseemed to render further lenity impossible, and a gentleman inmilitary dress, with a stout man of inferior rank, drew toward thedoor of the meetinghouse and awaited her approach. Scarcely did herfeet press the floor, however, when an unexpected scene occurred. Inthat moment of her peril, when every eye frowned with death, a littletimid boy threw his arms round his mother.

"I am here, mother; it is I, and I will go with thee to prison," heexclaimed.

She gazed at him with a doubtful and almost frightened expression, forshe knew that the boy had been cast out to perish, and she had nothoped to see his face again. She feared, perhaps, that it was but oneof the happy visions with which her excited fancy had often deceivedher in the solitude of the desert or in prison; but when she felt hishand warm within her own and heard his little eloquence of childishlove, she began to know that she was yet a mother.

"Blessed art thou, my son!" she sobbed. "My heart was withered--yea,dead with thee and with thy father--and now it leaps as in the firstmoment when I pressed thee to my bosom."

She knelt down and embraced him again and again, while the joy thatcould find no words expressed itself in broken accents, like thebubbles gushing up to vanish at the surface of a deep fountain. Thesorrows of past years and the darker peril that was nigh cast not ashadow on the brightness of that fleeting moment. Soon, however, thespectators saw a change upon her face as the consciousness of her sadestate returned, and grief supplied the fount of tears which joy hadopened. By the words she uttered it would seem that the indulgence ofnatural love had given her mind a momentary sense of its errors, andmade her know how far she had strayed from duty in following thedictates of a wild fanaticism.

"In a doleful hour art thou returned to me, poor boy," she said, "forthy mother's path has gone darkening onward, till now the end isdeath. Son, son, I have borne thee in my arms when my limbs weretottering, and I have fed thee with the food that I was fainting for;yet I have ill-performed a mother's part by thee in life, and now Ileave thee no inheritance but woe and shame. Thou wilt go seekingthrough the world, and find all hearts closed against thee and theirsweet affections turned to bitterness for my sake. My child, my child,how many a pang awaits thy gentle spirit, and I the cause of all!"

She hid her face on Ilbrahim's head, and her long raven hair,discolored with the ashes of her mourning, fell down about him like aveil. A low and interrupted moan was the voice of her heart's anguish,and it did not fail to move the sympathies of many who mistook theirinvoluntary virtue for a sin. Sobs were audible in the female sectionof the house, and every man who was a father drew his hand across hiseyes.

Tobias Pearson was agitated and uneasy, but a certain feeling like theconsciousness of guilt oppressed him; so that he could not go forthand offer himself as the protector of the child. Dorothy, however, hadwatched her husband's eye. Her mind was free from the influence thathad begun to work on his, and she drew near the Quaker woman andaddressed her in the hearing of all the congregation.

"Stranger, trust this boy to me, and I will be his mother," she said,taking Ilbrahim's hand. "Providence has signally marked out my husbandto protect him, and he has fed at our table and lodged under our roofnow many days, till our hearts have grown very strongly unto him.Leave the tender child with us, and be at ease concerning hiswelfare."

The Quaker rose from the ground, but drew the boy closer to her, whileshe gazed earnestly in Dorothy's face. Her mild but saddened featuresand neat matronly attire harmonized together and were like a verse offireside poetry. Her very aspect proved that she was blameless, so faras mortal could be so, in respect to God and man, while theenthusiast, in her robe of sackcloth and girdle of knotted cord, hadas evidently violated the duties of the present life and the future byfixing her attention wholly on the latter. The two females, as theyheld each a hand of Ilbrahim, formed a practical allegory: it wasrational piety and unbridled fanaticism contending for the empire of ayoung heart.

"Thou art not of our people," said the Quaker, mournfully.

"No, we are not of your people," replied Dorothy, with mildness, "butwe are Christians looking upward to the same heaven with you. Doubtnot that your boy shall meet you there, if there be a blessing on ourtender and prayerful guidance of him. Thither, I trust, my ownchildren have gone before me, for I also have been a mother. I am nolonger so," she added, in a faltering tone, "and your son will haveall my care."

"But will ye lead him in the path which his parents have trodden?"demanded the Quaker. "Can ye teach him the enlightened faith which hisfather has died for, and for which I--even I--am soon to become anunworthy martyr? The boy has been baptized in blood; will ye keep themark fresh and ruddy upon his forehead?"

"I will not deceive you," answered Dorothy. "If your child become ourchild, we must breed him up in the instruction which Heaven hasimparted to us; we must pray for him the prayers of our own faith; wemust do toward him according to the dictates of our own consciences,and not of yours. Were we to act otherwise, we should abuse yourtrust, even in complying with your wishes."

The mother looked down upon her boy with a troubled countenance, andthen turned her eyes upward to heaven. She seemed to pray internally,and the contention of her soul was evident.

"Friend," she said, at length, to Dorothy, "I doubt not that my sonshall receive all earthly tenderness at thy hands. Nay, I will believethat even thy imperfect lights may guide him to a better world, forsurely thou art on the path thither. But thou hast spoken of ahusband. Doth he stand here among this multitude of people? Let himcome forth, for I must know to whom I commit this most precioustrust."

She turned her face upon the male auditors, and after a momentarydelay Tobias Pearson came forth from among them. The Quaker saw thedress which marked his mi

litary rank, and shook her head; but then shenoted the hesitating air, the eyes that struggled with her own andwere vanquished, the color that went and came and could find noresting-place. As she gazed an unmirthful smile spread over herfeatures, like sunshine that grows melancholy in some desolate spot.Her lips moved inaudibly, but at length she spake:

"I hear it, I hear it! The voice speaketh within me and saith, 'Leavethy child, Catharine, for his place is here, and go hence, for I haveother work for thee. Break the bonds of natural affection, martyr thylove, and know that in all these things eternal wisdom hath its ends.'I go, friends, I go. Take ye my boy, my precious jewel. I go hencetrusting that all shall be well, and that even for his infant handsthere is a labor in the vineyard."

She knelt down and whispered to Ilbrahim, who at first struggled andclung to his mother with sobs and tears, but remained passive when shehad kissed his cheek and arisen from the ground. Having held her handsover his head in mental prayer, she was ready to depart.

"Farewell, friends in mine extremity," she said to Pearson and hiswife; "the good deed ye have done me is a treasure laid up in heaven,to be returned a thousandfold hereafter.--And farewell, ye mineenemies, to whom it is not permitted to harm so much as a hair of myhead, nor to stay my footsteps even for a moment. The day is comingwhen ye shall call upon me to witness for ye to this one sinuncommitted, and I will rise up and answer."

She turned her steps toward the door, and the men who had stationedthemselves to guard it withdrew and suffered her to pass. A generalsentiment of pity overcame the virulence of religious hatred.Sanctified by her love and her affliction, she went forth, and all thepeople gazed after her till she had journeyed up the hill and was lostbehind its brow. She went, the apostle of her own unquiet heart, torenew the wanderings of past years. For her voice had been alreadyheard in many lands of Christendom, and she had pined in the cells ofa Catholic Inquisition before she felt the lash and lay in thedungeons of the Puritans. Her mission had extended also to thefollowers of the Prophet, and from them she had received the courtesyand kindness which all the contending sects of our purer religionunited to deny her. Her husband and herself had resided many months inTurkey, where even the sultan's countenance was gracious to them; inthat pagan land, too, was Ilbrahim's birthplace, and his Oriental namewas a mark of gratitude for the good deeds of an unbeliever.

* * * * *

When Pearson and his wife had thus acquired all the rights overIlbrahim that could be delegated, their affection for him became, likethe memory of their native land or their mild sorrow for the dead, apiece of the immovable furniture of their hearts. The boy, also, aftera week or two of mental disquiet, began to gratify his protectors bymany inadvertent proofs that he considered them as parents and theirhouse as home. Before the winter snows were melted the persecutedinfant, the little wanderer from a remote and heathen country, seemednative in the New England cottage and inseparable from the warmth andsecurity of its hearth. Under the influence of kind treatment, and inthe consciousness that he was loved, Ilbrahim's demeanor lost apremature manliness which had resulted from his earlier situation; hebecame more childlike and his natural character displayed itself withfreedom. It was in many respects a beautiful one, yet the disorderedimaginations of both his father and mother had perhaps propagated acertain unhealthiness in the mind of the boy. In his general stateIlbrahim would derive enjoyment from the most trifling events and fromevery object about him; he seemed to discover rich treasures ofhappiness by a faculty analogous to that of the witch-hazel, whichpoints to hidden gold where all is barren to the eye. His airy gayety,coming to him from a thousand sources, communicated itself to thefamily, and Ilbrahim was like a domesticated sunbeam, brighteningmoody countenances and chasing away the gloom from the dark corners ofthe cottage.

On the other hand, as the susceptibility of pleasure is also that ofpain, the exuberant cheerfulness of the boy's prevailing tempersometimes yielded to moments of deep depression. His sorrows could notalways be followed up to their original source, but most frequentlythey appeared to flow--though Ilbrahim was young to be sad for such acause--from wounded love. The flightiness of his mirth rendered himoften guilty of offences against the decorum of a Puritan household,and on these occasions he did not invariably escape rebuke. But theslightest word of real bitterness, which he was infallible indistinguishing from pretended anger, seemed to sink into his heart andpoison all his enjoyments till he became sensible that he was entirelyforgiven. Of the malice which generally accompanies a superfluity ofsensitiveness Ilbrahim was altogether destitute. When trodden upon, hewould not turn; when wounded, he could but die. His mind was wantingin the stamina of self-support. It was a plant that would twinebeautifully round something stronger than itself; but if repulsed ortorn away, it had no choice but to wither on the ground. Dorothy'sacuteness taught her that severity would crush the spirit of thechild, and she nurtured him with the gentle care of one who handles abutterfly. Her husband manifested an equal affection, although it grewdaily less productive of familiar caresses.

The feelings of the neighboring people in regard to the Quaker infantand his protectors had not undergone a favorable change, in spite ofthe momentary triumph which the desolate mother had obtained overtheir sympathies. The scorn and bitterness of which he was the objectwere very grievous to Ilbrahim, especially when any circumstance madehim sensible that the children his equals in age partook of the enmityof their parents. His tender and social nature had already overflowedin attachments to everything about him, and still there was a residueof unappropriated love which he yearned to bestow upon the little oneswho were taught to hate him. As the warm days of spring came onIlbrahim was accustomed to remain for hours silent and inactive withinhearing of the children's voices at their play, yet with his usualdelicacy of feeling he avoided their notice, and would flee and hidehimself from the smallest individual among them. Chance, however, atlength seemed to open a medium of communication between his heart andtheirs; it was by means of a boy about two years older than Ilbrahim,who was injured by a fall from a tree in the vicinity of Pearson'shabitation. As the sufferer's own home was at some distance, Dorothywillingly received him under her roof and became his tender andcareful nurse.

Ilbrahim was the unconscious possessor of much skill in physiognomy,and it would have deterred him in other circumstances from attemptingto make a friend of this boy. The countenance of the latterimmediately impressed a beholder disagreeably, but it required someexamination to discover that the cause was a very slight distortion ofthe mouth and the irregular, broken line and near approach of theeyebrows. Analogous, perhaps, to these trifling deformities was analmost imperceptible twist of every joint and the uneven prominence ofthe breast, forming a body regular in its general outline, but faultyin almost all its details. The disposition of the boy was sullen andreserved, and the village schoolmaster stigmatized him as obtuse inintellect, although at a later period of life he evinced ambition andvery peculiar talents. But, whatever might be his personal or moralirregularities, Ilbrahim's heart seized upon and clung to him from themoment that he was brought wounded into the cottage; the child ofpersecution seemed to compare his own fate with that of the sufferer,and to feel that even different modes of misfortune had created a sortof relationship between them. Food, rest and the fresh air for whichhe languished were neglected; he nestled continually by the bedside ofthe little stranger and with a fond jealousy endeavored to be themedium of all the cares that were bestowed upon him. As the boy becameconvalescent Ilbrahim contrived games suitable to his situation oramused him by a faculty which he had perhaps breathed in with the airof his barbaric birthplace. It was that of reciting imaginaryadventures on the spur of the moment, and apparently in inexhaustiblesuccession. His tales were, of course, monstrous, disjointed andwithout aim, but they were curious on account of a vein of humantenderness which ran through them all and was like a sweet familiarface encountered in the midst of wild and unearthly scenery. Theauditor paid much a

ttention to these romances and sometimesinterrupted them by brief remarks upon the incidents, displayingshrewdness above his years, mingled with a moral obliquity whichgrated very harshly against Ilbrahim's instinctive rectitude. Nothing,however, could arrest the progress of the latter's affection, andthere were many proofs that it met with a response from the dark andstubborn nature on which it was lavished. The boy's parents at lengthremoved him to complete his cure under their own roof.

Ilbrahim did not visit his new friend after his departure, but he madeanxious and continual inquiries respecting him and informed himself ofthe day when he was to reappear among his playmates. On a pleasantsummer afternoon the children of the neighborhood had assembled in thelittle forest-crowned amphitheatre behind the meeting-house, and therecovering invalid was there, leaning on a staff. The glee of a scoreof untainted bosoms was heard in light and airy voices, which dancedamong the trees like sunshine become audible; the grown men of thisweary world as they journeyed by the spot marvelled why life,beginning in such brightness, should proceed in gloom, and theirhearts or their imaginations answered them and said that the bliss ofchildhood gushes from its innocence. But it happened that anunexpected addition was made to the heavenly little band. It wasIlbrahim, who came toward the children with a look of sweet confidenceon his fair and spiritual face, as if, having manifested his love toone of them, he had no longer to fear a repulse from their society. Ahush came over their mirth the moment they beheld him, and they stoodwhispering to each other while he drew nigh; but all at once the devilof their fathers entered into the unbreeched fanatics, and, sending upa fierce, shrill cry, they rushed upon the poor Quaker child. In aninstant he was the centre of a brood of baby-fiends, who lifted sticksagainst him, pelted him with stones and displayed an instinct ofdestruction far more loathsome than the bloodthirstiness of manhood.

The invalid, in the mean while, stood apart from the tumult, cryingout with a loud voice, "Fear not, Ilbrahim; come hither and take myhand," and his unhappy friend endeavored to obey him. After watchingthe victim's struggling approach with a calm smile and unabashed eye,the foul-hearted little villain lifted his staff and struck Ilbrahimon the mouth so forcibly that the blood issued in a stream. The poorchild's arms had been raised to guard his head from the storm ofblows, but now he dropped them at once. His persecutors beat him down,trampled upon him, dragged him by his long fair locks, and Ilbrahimwas on the point of becoming as veritable a martyr as ever enteredbleeding into heaven. The uproar, however, attracted the notice of afew neighbors, who put themselves to the trouble of rescuing thelittle heretic, and of conveying him to Pearson's door.

Ilbrahim's bodily harm was severe, but long and careful nursingaccomplished his recovery; the injury done to his sensitive spirit wasmore serious, though not so visible. Its signs were principally of anegative character, and to be discovered only by those who hadpreviously known him. His gait was thenceforth slow, even and unvariedby the sudden bursts of sprightlier motion which had once correspondedto his overflowing gladness; his countenance was heavier, and itsformer play of expression--the dance of sunshine reflected from movingwater--was destroyed by the cloud over his existence; his notice wasattracted in a far less degree by passing events, and he appeared tofind greater difficulty in comprehending what was new to him than at ahappier period. A stranger founding his judgment upon thesecircumstances would have said that the dulness of the child'sintellect widely contradicted the promise of his features, but thesecret was in the direction of Ilbrahim's thoughts, which werebrooding within him when they should naturally have been wanderingabroad. An attempt of Dorothy to revive his former sportiveness wasthe single occasion on which his quiet demeanor yielded to a violentdisplay of grief; he burst into passionate weeping and ran and hidhimself, for his heart had become so miserably sore that even the handof kindness tortured it like fire. Sometimes at night, and probably inhis dreams, he was heard to cry, "Mother! Mother!" as if her place,which a stranger had supplied while Ilbrahim was happy, admitted of nosubstitute in his extreme affliction. Perhaps among the manylife-weary wretches then upon the earth there was not one who combinedinnocence and misery like this poor broken-hearted infant so soon thevictim of his own heavenly nature.

While this melancholy change had taken place in Ilbrahim, one of anearlier origin and of different character had come to its perfectionin his adopted father. The incident with which this tale commencesfound Pearson in a state of religious dulness, yet mentally disquietedand longing for a more fervid faith than he possessed. The firsteffect of his kindness to Ilbrahim was to produce a softened feeling,an incipient love for the child's whole sect, but joined to this, andresulting, perhaps, from self-suspicion, was a proud and ostentatiouscontempt of their tenets and practical extravagances. In the course ofmuch thought, however--for the subject struggled irresistibly into hismind--the foolishness of the doctrine began to be less evident, andthe points which had particularly offended his reason assumed anotheraspect or vanished entirely away. The work within him appeared to goon even while he slept, and that which had been a doubt when he laiddown to rest would often hold the place of a truth confirmed by someforgotten demonstration when he recalled his thoughts in the morning.But, while he was thus becoming assimilated to the enthusiasts, hiscontempt, in nowise decreasing toward them, grew very fierce againsthimself; he imagined, also, that every face of his acquaintance wore asneer, and that every word addressed to him was a gibe. Such was hisstate of mind at the period of Ilbrahim's misfortune, and the emotionsconsequent upon that event completed the change of which the child hadbeen the original instrument.

In the mean time, neither the fierceness of the persecutors nor theinfatuation of their victims had decreased. The dungeons were neverempty; the streets of almost every village echoed daily with the lash;the life of a woman whose mild and Christian spirit no cruelty couldembitter had been sacrificed, and more innocent blood was yet topollute the hands that were so often raised in prayer. Early after theRestoration the English Quakers represented to Charles II. that a"vein of blood was open in his dominions," but, though the displeasureof the voluptuous king was roused, his interference was not prompt.And now the tale must stride forward over many months, leaving Pearsonto encounter ignominy and misfortune; his wife, to a firm endurance ofa thousand sorrows; poor Ilbrahim, to pine and droop like a cankeredrose-bud; his mother, to wander on a mistaken errand, neglectful ofthe holiest trust which can be committed to a woman.

* * * * *

A winter evening, a night of storm, had darkened over Pearson'shabitation, and there were no cheerful faces to drive the gloom fromhis broad hearth. The fire, it is true, sent forth a glowing heat anda ruddy light, and large logs dripping with half-melted snow lay readyto cast upon the embers. But the apartment was saddened in its aspectby the absence of much of the homely wealth which had once adorned it,for the exaction of repeated fines and his own neglect of temporalaffairs had greatly impoverished the owner. And with the furniture ofpeace the implements of war had likewise disappeared; the sword wasbroken, the helm and cuirass were cast away for ever: the soldier haddone with battles, and might not lift so much as his naked hand toguard his head. But the Holy Book remained, and the table on which itrested was drawn before the fire, while two of the persecuted sectsought comfort from its pages.

He who listened while the other read was the master of the house, nowemaciated in form and altered as to the expression and healthiness ofhis countenance, for his mind had dwelt too long among visionarythoughts and his body had been worn by imprisonment and stripes. Thehale and weatherbeaten old man who sat beside him had sustained lessinjury from a far longer course of the same mode of life. In person hewas tall and dignified, and, which alone would have made him hatefulto the Puritans, his gray locks fell from beneath the broad-brimmedhat and rested on his shoulders. As the old man read the sacred pagethe snow drifted against the windows or eddied in at the crevices ofthe door, while a blast kept laughing in the chimney and the blazel

eaped fiercely up to seek it. And sometimes, when the wind struck thehill at a certain angle and swept down by the cottage across thewintry plain, its voice was the most doleful that can be conceived; itcame as if the past were speaking, as if the dead had contributed eacha whisper, as if the desolation of ages were breathed in that onelamenting sound.

The Quaker at length closed the book, retaining, however, his handbetween the pages which he had been reading, while he lookedsteadfastly at Pearson. The attitude and features of the latter mighthave indicated the endurance of bodily pain; he leaned his forehead onhis hands, his teeth were firmly closed and his frame was tremulous atintervals with a nervous agitation.

"Friend Tobias," inquired the old man, compassionately, "hast thoufound no comfort in these many blessed passages of Scripture?"

"Thy voice has fallen on my ear like a sound afar off and indistinct,"replied Pearson, without lifting his eyes. "Yea; and when I havehearkened carefully, the words seemed cold and lifeless and intendedfor another and a lesser grief than mine. Remove the book," he added,in a tone of sullen bitterness; "I have no part in its consolations,and they do but fret my sorrow the more."

"Nay, feeble brother; be not as one who hath never known the light,"said the elder Quaker, earnestly, but with mildness. "Art thou he thatwouldst be content to give all and endure all for conscience' sake,desiring even peculiar trials that thy faith might be purified and thyheart weaned from worldly desires? And wilt thou sink beneath anaffliction which happens alike to them that have their portion herebelow and to them that lay up treasure in heaven? Faint not, for thyburden is yet light."

"It is heavy! It is heavier than I can bear!" exclaimed Pearson, withthe impatience of a variable spirit. "From my youth upward I have beena man marked out for wrath, and year by year--yea, day after day--Ihave endured sorrows such as others know not in their lifetime. Andnow I speak not of the love that has been turned to hatred, the honorto ignominy, the ease and plentifulness of all things to danger, wantand nakedness. All this I could have borne and counted myself blessed.But when my heart was desolate with many losses, I fixed it upon thechild of a stranger, and he became dearer to me than all my buriedones; and now he too must die as if my love were poison. Verily, I aman accursed man, and I will lay me down in the dust and lift up myhead no more."

"Thou sinnest, brother, but it is not for me to rebuke thee, for Ialso have had my hours of darkness wherein I have murmured against thecross," said the old Quaker. He continued, perhaps in the hope ofdistracting his companion's thoughts from his own sorrows: "Even oflate was the light obscured within me, when the men of blood hadbanished me on pain of death and the constables led me onward fromvillage to village toward the wilderness. A strong and cruel hand waswielding the knotted cords; they sunk deep into the flesh, and thoumightst have tracked every reel and totter of my footsteps by theblood that followed. As we went on--"

"Have I not borne all this, and have I murmured?" interrupted Pearson,impatiently.

"Nay, friend, but hear me," continued the other. "As we journeyed onnight darkened on our path, so that no man could see the rage of thepersecutors or the constancy of my endurance, though Heaven forbidthat I should glory therein. The lights began to glimmer in thecottage windows, and I could discern the inmates as they gathered incomfort and security, every man with his wife and children by theirown evening hearth. At length we came to a tract of fertile land. Inthe dim light the forest was not visible around it, and, behold, therewas a straw-thatched dwelling which bore the very aspect of my homefar over the wild ocean--far in our own England. Then came bitterthoughts upon me--yea, remembrances that were like death to my soul.The happiness of my early days was painted to me, the disquiet of mymanhood, the altered faith of my declining years. I remembered how Ihad been moved to go forth a wanderer when my daughter, the youngest,the dearest of my flock, lay on her dying-bed, and--"

"Couldst thou obey the command at such a moment?" exclaimed Pearson,shuddering.

"Yea! yea!" replied the old man, hurriedly. "I was kneeling by herbedside when the voice spoke loud within me, but immediately I roseand took my staff and gat me gone. Oh that it were permitted me toforget her woeful look when I thus withdrew my arm and left herjourneying through the dark valley alone! for her soul was faint andshe had leaned upon my prayers. Now in that night of horror I wasassailed by the thought that I had been an erring Christian and acruel parent; yea, even my daughter with her pale dying featuresseemed to stand by me and whisper, 'Father, you are deceived; go homeand shelter your gray head.'--O Thou to whom I have looked in myfurthest wanderings," continued the Quaker, raising his agitated eyesto heaven, "inflict not upon the bloodiest of our persecutors theunmitigated agony of my soul when I believed that all I had done andsuffered for thee was at the instigation of a mocking fiend!--But Iyielded not; I knelt down and wrestled with the tempter, while thescourge bit more fiercely into the flesh. My prayer was heard, and Iwent on in peace and joy toward the wilderness."

The old man, though his fanaticism had generally all the calmness ofreason, was deeply moved while reciting this tale, and his unwontedemotion seemed to rebuke and keep down that of his companion. They satin silence, with their faces to the fire, imagining, perhaps, in itsred embers new scenes of persecution yet to be encountered. The snowstill drifted hard against the windows, and sometimes, as the blaze ofthe logs had gradually sunk, came down the spacious chimney and hissedupon the hearth. A cautious footstep might now and then be heard in aneighboring apartment, and the sound invariably drew the eyes of bothQuakers to the door which led thither. When a fierce and riotous gustof wind had led his thoughts by a natural association to homelesstravellers on such a night, Pearson resumed the conversation.

"I have wellnigh sunk under my own share of this trial," observed he,sighing heavily; "yet I would that it might be doubled to me, if sothe child's mother could be spared. Her wounds have been deep andmany, but this will be the sorest of all."

"Fear not for Catharine," replied the old Quaker, "for I know thatvaliant woman and have seen how she can bear the cross. A mother'sheart, indeed, is strong in her, and may seem to contend mightily withher faith; but soon she will stand up and give thanks that her son hasbeen thus early an accepted sacrifice. The boy hath done his work, andshe will feel that he is taken hence in kindness both to him and her.Blessed, blessed are they that with so little suffering can enter intopeace!"

The fitful rush of the wind was now disturbed by a portentous sound:it was a quick and heavy knocking at the outer door. Pearson's wancountenance grew paler, for many a visit of persecution had taught himwhat to dread; the old man, on the other hand, stood up erect, and hisglance was firm as that of the tried soldier who awaits his enemy.

"The men of blood have come to seek me," he observed, with calmness."They have heard how I was moved to return from banishment, and now amI to be led to prison, and thence to death. It is an end I have longlooked for. I will open unto them lest they say, 'Lo, he feareth!'"

"Nay; I will present myself before them," said Pearson, with recoveredfortitude. "It may be that they seek me alone and know not that thouabidest with me."

"Let us go boldly, both one and the other," rejoined his companion."It is not fitting that thou or I should shrink."

They therefore proceeded through the entry to the door, which theyopened, bidding the applicant "Come in, in God's name!" A furiousblast of wind drove the storm into their faces and extinguished thelamp; they had barely time to discern a figure so white from head tofoot with the drifted snow that it seemed like Winter's self come inhuman shape to seek refuge from its own desolation.

"Enter, friend, and do thy errand, be it what it may," said Pearson."It must needs be pressing, since thou comest on such a bitter night."

"Peace be with this household!" said the stranger, when they stood onthe floor of the inner apartment.

Pearson started; the elder Quaker stirred the slumbering embers of thefire till they sent up a clear and lofty blaze. It was a female

voicethat had spoken; it was a female form that shone out, cold and wintry,in that comfortable light.

"Catharine, blessed woman," exclaimed the old man, "art thou come tothis darkened land again? Art thou come to bear a valiant testimony asin former years? The scourge hath not prevailed against thee, andfrom the dungeon hast thou come forth triumphant, but strengthen,strengthen now thy heart, Catharine, for Heaven will prove thee yetthis once ere thou go to thy reward."

"Rejoice, friends!" she replied. "Thou who hast long been of ourpeople, and thou whom a little child hath led to us, rejoice! Lo, Icome, the messenger of glad tidings, for the day of persecution isover-past. The heart of the king, even Charles, hath been moved ingentleness toward us, and he hath sent forth his letters to stay thehands of the men of blood. A ship's company of our friends hatharrived at yonder town, and I also sailed joyfully among them."

As Catharine spoke her eyes were roaming about the room in search ofhim for whose sake security was dear to her. Pearson made a silentappeal to the old man, nor did the latter shrink from the painful taskassigned him.

"Sister," he began, in a softened yet perfectly calm tone, "thoutellest us of his love manifested in temporal good, and now must wespeak to thee of that selfsame love displayed in chastenings.Hitherto, Catharine, thou hast been as one journeying in a darksomeand difficult path and leading an infant by the hand; fain wouldstthou have looked heavenward continually, but still the cares of thatlittle child have drawn thine eyes and thy affections to the earth.Sister, go on rejoicing, for his tottering footsteps shall impedethine own no more."

But the unhappy mother was not thus to be consoled. She shook like aleaf; she turned white as the very snow that hung drifted into herhair. The firm old man extended his hand and held her up, keeping hiseye upon hers as if to repress any outbreak of passion.

"I am a woman--I am but a woman; will He try me above my strength?"said Catharine, very quickly and almost in a whisper. "I have beenwounded sore; I have suffered much--many things in the body, many inthe mind; crucified in myself and in them that were dearest to me.Surely," added she, with a long shudder, "he hath spared me in thisone thing." She broke forth with sudden and irrepressible violence:"Tell me, man of cold heart, what has God done to me? Hath he castme down never to rise again? Hath he crushed my very heart in hishand?--And thou to whom I committed my child, how hast thou fulfilledthy trust? Give me back the boy well, sound, alive--alive--or earthand heaven shall avenge me!"

The agonized shriek of Catharine was answered by the faint--the veryfaint--voice of a child.

On this day it had become evident to Pearson, to his aged guest and toDorothy that Ilbrahim's brief and troubled pilgrimage drew near itsclose. The two former would willingly have remained by him to make useof the prayers and pious discourses which they deemed appropriate tothe time, and which, if they be impotent as to the departingtraveller's reception in the world whither he goes, may at leastsustain him in bidding adieu to earth. But, though Ilbrahim uttered nocomplaint, he was disturbed by the faces that looked upon him; so thatDorothy's entreaties and their own conviction that the child's feetmight tread heaven's pavement and not soil it had induced the twoQuakers to remove. Ilbrahim then closed his eyes and grew calm, and,except for now and then a kind and low word to his nurse, might havebeen thought to slumber. As nightfall came on, however, and the stormbegan to rise, something seemed to trouble the repose of the boy'smind and to render his sense of hearing active and acute. If a passingwind lingered to shake the casement, he strove to turn his head towardit; if the door jarred to and fro upon its hinges, he looked long andanxiously thitherward; if the heavy voice of the old man as he readthe Scriptures rose but a little higher, the child almost held hisdying-breath to listen; if a snowdrift swept by the cottage with asound like the trailing of a garment, Ilbrahim seemed to watch thatsome visitant should enter. But after a little time he relinquishedwhatever secret hope had agitated him and with one low complainingwhisper turned his cheek upon the pillow. He then addressed Dorothywith his usual sweetness and besought her to draw near him; she didso, and Ilbrahim took her hand in both of his, grasping it with agentle pressure, as if to assure himself that he retained it. Atintervals, and without disturbing the repose of his countenance, avery faint trembling passed over him from head to foot, as if a mildbut somewhat cool wind had breathed upon him and made him shiver.

As the boy thus led her by the hand in his quiet progress over theborders of eternity, Dorothy almost imagined that she could discernthe near though dim delightfulness of the home he was about to reach;she would not have enticed the little wanderer back, though shebemoaned herself that she must leave him and return. But just whenIlbrahim's feet were pressing on the soil of Paradise he heard a voicebehind him, and it recalled him a few, few paces of the weary pathwhich he had travelled. As Dorothy looked upon his features sheperceived that their placid expression was again disturbed. Her ownthoughts had been so wrapped in him that all sounds of the storm andof human speech were lost to her; but when Catharine's shriek piercedthrough the room, the boy strove to raise himself.

"Friend, she is come! Open unto her!" cried he.

In a moment his mother was kneeling by the bedside; she drew Ilbrahimto her bosom, and he nestled there with no violence of joy, butcontentedly as if he were hushing himself to sleep. He looked into herface, and, reading its agony, said with feeble earnestness,

"Mourn not, dearest mother. I am happy now;" and with these words thegentle boy was dead.

* * * * *

The king's mandate to stay the New England persecutors was effectualin preventing further martyrdoms, but the colonial authorities,trusting in the remoteness of their situation, and perhaps in thesupposed instability of the royal government, shortly renewed theirseverities in all other respects. Catharine's fanaticism had becomewilder by the sundering of all human ties; and wherever a scourge waslifted, there was she to receive the blow; and whenever a dungeon wasunbarred, thither she came to cast herself upon the floor. But inprocess of time a more Christian spirit--a spirit of forbearance,though not of cordiality or approbation--began to pervade the land inregard to the persecuted sect. And then, when the rigid old Pilgrimseyed her rather in pity than in wrath, when the matrons fed her withthe fragments of their children's food and offered her a lodging on ahard and lowly bed, when no little crowd of schoolboys left theirsports to cast stones after the roving enthusiast,--then did Catharinereturn to Pearson's dwelling, and made that her home.

As if Ilbrahim's sweetness yet lingered round his ashes, as if hisgentle spirit came down from heaven to teach his parent a truereligion, her fierce and vindictive nature was softened by the samegriefs which had once irritated it. When the course of years had madethe features of the unobtrusive mourner familiar in the settlement,she became a subject of not deep but general interest--a being on whomthe otherwise superfluous sympathies of all might be bestowed. Everyone spoke of her with that degree of pity which it is pleasant toexperience; every one was ready to do her the little kindnesses whichare not costly, yet manifest good-will; and when at last she died, along train of her once bitter persecutors followed her with decentsadness and tears that were not painful to her place by Ilbrahim'sgreen and sunken grave.

The Scarlet Letter

The Scarlet Letter Young Goodman Brown : By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated

Young Goodman Brown : By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated The Birthmark

The Birthmark The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 1

The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 1 The Minister's Black Veil

The Minister's Black Veil The Great Stone Face, and Other Tales of the White Mountains

The Great Stone Face, and Other Tales of the White Mountains The House of the Seven Gables

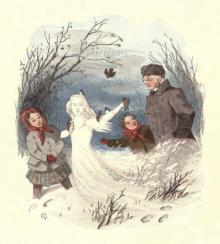

The House of the Seven Gables The Snow Image

The Snow Image The Blithedale Romance

The Blithedale Romance Rappaccini's Daughter: By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated

Rappaccini's Daughter: By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated Twice-Told Tales

Twice-Told Tales Twice Told Tales

Twice Told Tales The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 2

The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 2_preview.jpg) Footprints on the Sea-Shore (From Twice Told Tales)

Footprints on the Sea-Shore (From Twice Told Tales) Main Street

Main Street_preview.jpg) The Seven Vagabonds (From Twice Told Tales)

The Seven Vagabonds (From Twice Told Tales) Fanshawe

Fanshawe Chippings with a Chisel

Chippings with a Chisel Selected Tales and Sketches

Selected Tales and Sketches Young Goodman Brown

Young Goodman Brown Roger Malvin's Burial

Roger Malvin's Burial The Prophetic Pictures

The Prophetic Pictures The Village Uncle

The Village Uncle Scarlet Letter (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Scarlet Letter (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Procession of Life

The Procession of Life Drowne's Wooden Image

Drowne's Wooden Image Hawthorne's Short Stories

Hawthorne's Short Stories My Kinsman, Major Molineux

My Kinsman, Major Molineux Legends of the Province House

Legends of the Province House Foot-Prints on the Sea-Shore

Foot-Prints on the Sea-Shore The Haunted Quack

The Haunted Quack Tanglewood Tales

Tanglewood Tales The Seven Vagabonds

The Seven Vagabonds Mosses from an Old Manse, Volume 2

Mosses from an Old Manse, Volume 2 The Canterbury Pilgrims

The Canterbury Pilgrims Wakefield

Wakefield The Gray Champion

The Gray Champion The White Old Maid

The White Old Maid The Snow-Image: A Childish Miracle

The Snow-Image: A Childish Miracle The Gentle Boy

The Gentle Boy Mr. Higginbotham's Catastrophe

Mr. Higginbotham's Catastrophe![The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/the_threefold_destiny_a_fairy_legend_by_ashley_allen_royce_pseud__preview.jpg) The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.]

The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.] Lady Eleanore`s Mantle

Lady Eleanore`s Mantle The Great Carbuncle

The Great Carbuncle The Portable Hawthorne (Penguin Classics)

The Portable Hawthorne (Penguin Classics) True Stories from History and Biography

True Stories from History and Biography