- Home

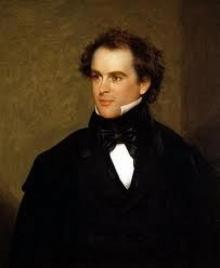

- Nathaniel Hawthorne

Main Street Page 7

Main Street Read online

Page 7

been quaffed. Else why should the bearers stagger, asthey tremulously uphold the coffin?--and the aged pall-bearers, too, asthey strive to walk solemnly beside it?--and wherefore do the mournerstread on one another's heels?--and why, if we may ask without offence,should the nose of the Rev. Mr. Noyes, through which he has just beendelivering the funeral discourse, glow like a ruddy coal of fire? Well,well, old friends! Pass on, with your burden of mortality, And lay it inthe tomb with jolly hearts. People should be permitted to enjoythemselves in their own fashion; every man to his taste; but New Englandmust have been a dismal abode for the man of pleasure, when the onlyboon-companion was Death!

Under cover of a mist that has settled over the scene, a few years flitby, and escape our notice. As the atmosphere becomes transparent, weperceive a decrepit grandsire, hobbling along the street. Do yourecognize him? We saw him, first, as the baby in Goodwife Massey's arms,when the primeval trees were flinging their shadow over Roger Conant'scabin; we have seen him, as the boy, the youth, the man, bearing hishumble part in all the successive scenes, and forming the index-figurewhereby to note the age of his coeval town. And here he is, old GoodmanMassey, taking his last walk,--often pausing,--often leaning over hisstaff,--and calling to mind whose dwelling stood at such and such a spot,and whose field or garden occupied the site of those more recent houses.He can render a reason for all the bends and deviations of thethoroughfare, which, in its flexible and plastic infancy, was made toswerve aside from a straight line, in order to visit every settler'sdoor. The Main Street is still youthful; the coeval man is in his latestage. Soon he will be gone, a patriarch of fourscore, yet shall retain asort of infantine life in our local history, as the first town-bornchild.

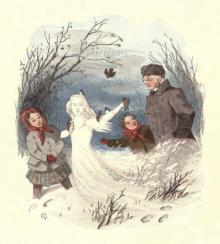

Behold here a change, wrought in the twinkling of an eye, like anincident in a tale of magic, even while your observation has been fixedupon the scene. The Main Street has vanished out of sight. In its steadappears a wintry waste of snow, with the sun just peeping over it, coldand bright, and tingeing the white expanse with the faintest and mostethereal rose-color. This is the Great Snow of 1717, famous for themountain-drifts in which it buried the whole country. It would seem asif the street, the growth of which we have noted so attentively,following it from its first phase, as an Indian track, until it reachedthe dignity of sidewalks, were all at once obliterated, and resolved intoa drearier pathlessness than when the forest covered it. The giganticswells and billows of the snow have swept over each man's metes andbounds, and annihilated all the visible distinctions of human property.So that now the traces of former times and hitherto accomplished deedsbeing done away, mankind should be at liberty to enter on new paths, andguide themselves by other laws than heretofore; if, indeed, the race benot extinct, and it be worth our while to go on with the march of life,over the cold and desolate expanse that lies before us. It may be,however, that matters are not so desperate as they appear. That vasticicle, glittering so cheerlessly in the sunshine, must be the spire ofthe meeting-house, incrusted with frozen sleet. Those great heaps, too,which we mistook for drifts, are houses, buried up to their eaves, andwith their peaked roofs rounded by the depth of snow upon them. There,now, comes a gush of smoke from what I judge to be the chimney of theShip Tavern;--and another--another--and another--from the chimneys ofother dwellings, where fireside comfort, domestic peace, the sports ofchildren, and the quietude of age are living yet, in spite of the frozencrust above them.

But it is time to change the scene. Its dreary monotony shall not testyour fortitude like one of our actual New England winters, which leavesso large a blank--so melancholy a death-spot-in lives so brief that theyought to be all summer-time. Here, at least, I may claim to be ruler ofthe seasons. One turn of the crank shall melt away the snow from theMain Street, and show the trees in their full foliage, the rose-bushes inbloom, and a border of green grass along the sidewalk. There! But what!How! The scene will not move. A wire is broken. The street continuesburied beneath the snow, and the fate of Herculaneum and Pompeii has itsparallel in this catastrophe.

Alas! my kind and gentle audience, you know not the extent of yourmisfortune. The scenes to come were far better than the past. Thestreet itself would have been more worthy of pictorial exhibition; thedeeds of its inhabitants not less so. And how would your interest havedeepened, as, passing out of the cold shadow of antiquity, in my long andweary course, I should arrive within the limits of man's memory, and,leading you at last into the sunshine of the present, should give areflex of the very life that is flitting past us! Your own beauty, myfair townswomen, would have beamed upon you, out of my scene. Not agentleman that walks the street but should have beheld his own face andfigure, his gait, the peculiar swing of his arm, and the coat that he puton yesterday. Then, too,--and it is what I chiefly regret,--I hadexpended a vast deal of light and brilliancy on a representation of thestreet in its whole length, from Buffum's Corner downward, on the nightof the grand illumination for General Taylor's triumph. Lastly, I shouldhave given the crank one other turn, and have brought out the future,showing you who shall walk the Main Street to-morrow, and, perchance,whose funeral shall pass through it!

But these, like most other human purposes, lie unaccomplished; and I haveonly further to say, that any lady or gentlemen who may feel dissatisfiedwith the evening's entertainment shall receive back the admission fee atthe door.

"Then give me mine," cries the critic, stretching out his palm. "I saidthat your exhibition would prove a humbug, and so it has turned out. So,hand over my quarter!"

The Scarlet Letter

The Scarlet Letter Young Goodman Brown : By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated

Young Goodman Brown : By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated The Birthmark

The Birthmark The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 1

The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 1 The Minister's Black Veil

The Minister's Black Veil The Great Stone Face, and Other Tales of the White Mountains

The Great Stone Face, and Other Tales of the White Mountains The House of the Seven Gables

The House of the Seven Gables The Snow Image

The Snow Image The Blithedale Romance

The Blithedale Romance Rappaccini's Daughter: By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated

Rappaccini's Daughter: By Nathaniel Hawthorne - Illustrated Twice-Told Tales

Twice-Told Tales Twice Told Tales

Twice Told Tales The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 2

The Marble Faun; Or, The Romance of Monte Beni - Volume 2_preview.jpg) Footprints on the Sea-Shore (From Twice Told Tales)

Footprints on the Sea-Shore (From Twice Told Tales) Main Street

Main Street_preview.jpg) The Seven Vagabonds (From Twice Told Tales)

The Seven Vagabonds (From Twice Told Tales) Fanshawe

Fanshawe Chippings with a Chisel

Chippings with a Chisel Selected Tales and Sketches

Selected Tales and Sketches Young Goodman Brown

Young Goodman Brown Roger Malvin's Burial

Roger Malvin's Burial The Prophetic Pictures

The Prophetic Pictures The Village Uncle

The Village Uncle Scarlet Letter (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Scarlet Letter (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Procession of Life

The Procession of Life Drowne's Wooden Image

Drowne's Wooden Image Hawthorne's Short Stories

Hawthorne's Short Stories My Kinsman, Major Molineux

My Kinsman, Major Molineux Legends of the Province House

Legends of the Province House Foot-Prints on the Sea-Shore

Foot-Prints on the Sea-Shore The Haunted Quack

The Haunted Quack Tanglewood Tales

Tanglewood Tales The Seven Vagabonds

The Seven Vagabonds Mosses from an Old Manse, Volume 2

Mosses from an Old Manse, Volume 2 The Canterbury Pilgrims

The Canterbury Pilgrims Wakefield

Wakefield The Gray Champion

The Gray Champion The White Old Maid

The White Old Maid The Snow-Image: A Childish Miracle

The Snow-Image: A Childish Miracle The Gentle Boy

The Gentle Boy Mr. Higginbotham's Catastrophe

Mr. Higginbotham's Catastrophe![The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/the_threefold_destiny_a_fairy_legend_by_ashley_allen_royce_pseud__preview.jpg) The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.]

The Threefold Destiny: A Fairy Legend, by Ashley Allen Royce [pseud.] Lady Eleanore`s Mantle

Lady Eleanore`s Mantle The Great Carbuncle

The Great Carbuncle The Portable Hawthorne (Penguin Classics)

The Portable Hawthorne (Penguin Classics) True Stories from History and Biography

True Stories from History and Biography